After the demise of Oceanside’s first wharf in 1890, the beach was covered with its debris. Rather than let the lumber float away, or rot in the sand, Melchior Pieper, proprietor of the grand and beautiful South Pacific Hotel, began collecting the pilings and planks. He loaded them up on wagons and stored the material behind his hotel. Pieper even stamped his initials on the pilings and lumber.

What was his intention? He was looking to build interest and financial support for a new wharf to be built at the end of Third Street (Pier View Way). It would be beneficial to have a wharf at that location, attracting more business and more guests to the hotel, which was located just north of Third Street, but also moving the pier to a more central location in Oceanside’s small downtown.

Determined, Pieper even traveled to San Francisco in December of 1893 to meet with Anson P. Hotaling, owner of the South Pacific Hotel, (as well as considerable property throughout the city and South Oceanside) to attempt to persuade him to support the building a pier that would be beneficial for the hotel. Pieper’s trip was successful, as Hotaling agreed to support the construction of a wharf.

In April of 1894 a committee was formed and plans for the new wharf began. There was some resistance against the Third Street location, (a site between Second and Third was favored), but with Hotaling donating $350 and Pieper donating $100 and offering to board the workmen free, the disagreement was set aside.

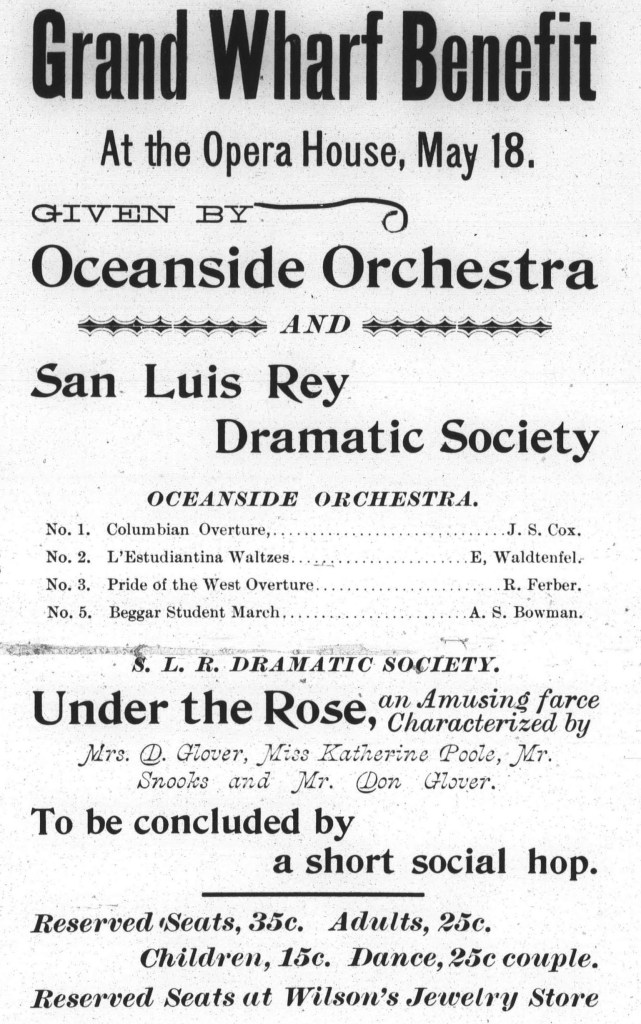

Modest fundraising began with the Oceanside Silver Cornet Band holding a benefit ball at the Oceanside Opera House. Tickets were just a dollar but the Benefit, hailed as a success, and raised $50 for the wharf fund.

Specifications for the new pier were listed in the local paper: “The wharf will be 400 feet long from high water mark, 12 feet wide, and four inch iron pipe will be used for piling, which will be strongly braced. It will be floored with two inch planing and a wooden railing of 3 x 4 material will surmount it. The entire length from the bluff will be about 600 feet. The total cost will be about $1200.“

By June over $1,000 was pledged and two weeks of labor donated. John A. Tulip, a member of the wharf committee, persuaded a resident in joining him in digging the first hole for one of the pilings to be used in the wharf’s approach. Within days several bents and stringers were put in place and 200 feet of the approach were ready for flooring.

In June the wharf committee ordered 440 feet of iron pipe, which arrived from St. Louis in August. In September of 1894 the Oceanside Blade reported that, “Work on the wharf is at last underway. An overhang derrick, as it is called, has been constructed by Mr. Cook, the piles have been asphalted, the joints been banded and strengthened and the work of putting them in place begun.”

Work was done quickly, largely due to the diminished length of the new structure. Oceanside’s second pier was known as the “iron” wharf because of the iron that braced its pilings. When finished, the little iron wharf measured at a modest length of just over 600 feet.

The new pier was not without its hazards, as there was no railing added for the safety of fishermen, pedestrians and especially small children. Even after a railing was added in February of 1895, there is some speculation as to how really safe it was.

In August of that year 14-year-old Fannie Halloran was a near victim after she fell from the pier, as the Blade reported: [Fannie] “while fishing on the wharf last Saturday, caught a fish and in trying to land it got the line fastened about one of the pile, and, in leaning over trying to get it loose, lost her balance and took a header to the water below, a distance of about 14 feet. She had learned recently to swim, immediately applied her knowledge in the direction to getting ashore, which, with some assistance from her father was easily accomplished. No injury resulted, but quite a different report would no doubt have been the result had the young lady not exhibited great coolness and presence of mind.”

Still, Oceanside’s new wharf was popular with residents and visitors as the Blade noted, “A great many people from the back country are enjoying fishing from the wharf here. It is a great attraction and the best investment the people of this place ever made.”

But noting that the approaching Independence Day celebration and festivities it also added: “We should not forget the wharf, and its further extension into the Occident. [The] wharf is an investment that is an all-the-year standby. It will bring people as no other attraction here will or can. Fishing is almost a passion with many, and from observation often confirmed, it is–by virtue of the little iron wharf at the foot of Third Street–a source of the only meat supply of many others. But its length will not warrant many persons fishing at once, and for boating facilities, for the same cause, it affords none. The season should not be permitted to go by without extending it at least 200 feet further. As an investment to the town it is worth ten celebrations.”

That July 4th celebration in 1895 was a success but only highlighted the need for a longer pier, prompting a meeting by city leaders: “Dr. Nichols explained the call of the meeting to be for the above purpose and gave estimates which he had carefully compiled, based upon what work and expense had already been done. The amount necessary to extend the wharf two hundred feet further would entail an expenditure of close to six hundred dollars. He went on to state in his most eloquent fashion, the large benefit the wharf had already been to the city of Oceanside and that there was an assurance of a large number of families who would spend the summer here, and the cause of this was that Oceansiders were awake to the fact that to get the people from the hot interior towns to spend the heated, term, here, that inducements in the way of a pleasure and fishing wharf was an absolute necessity in connection with our natural inducements of climate, location, etc.“

Talk continued to extend the wharf, one hundred, two hundred and even three hundred feet but nothing was done because of lack of funding. However, on September 17, 1896, Matthew W. Spencer and Melchior Pieper, members of the wharf’s Executive Committee, officially deeded the pier to the City of Oceanside.

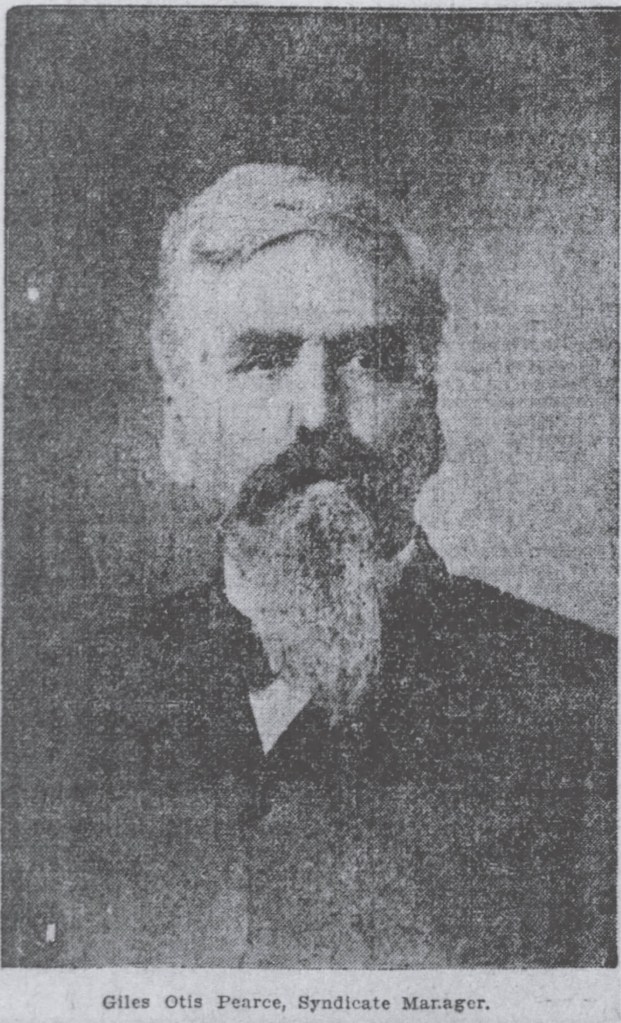

In May of 1897, Giles Otis Pearce, a self-described “assayer, metallurgist and mining expert” from Colorado, collaborated with Oceanside inventor Wilton S. Schuyler, son of businessman John Schuyler.

A legitimate inventor, Wilton actually designed and built an early automobile in 1898 which he called the “Oceanside Express.” He received a patent for the vehicle in 1899. He then invented and patented a “wave motor” which Pearce wanted to use for a dubious method to extract gold from the ocean after it was affixed to the Oceanside pier.

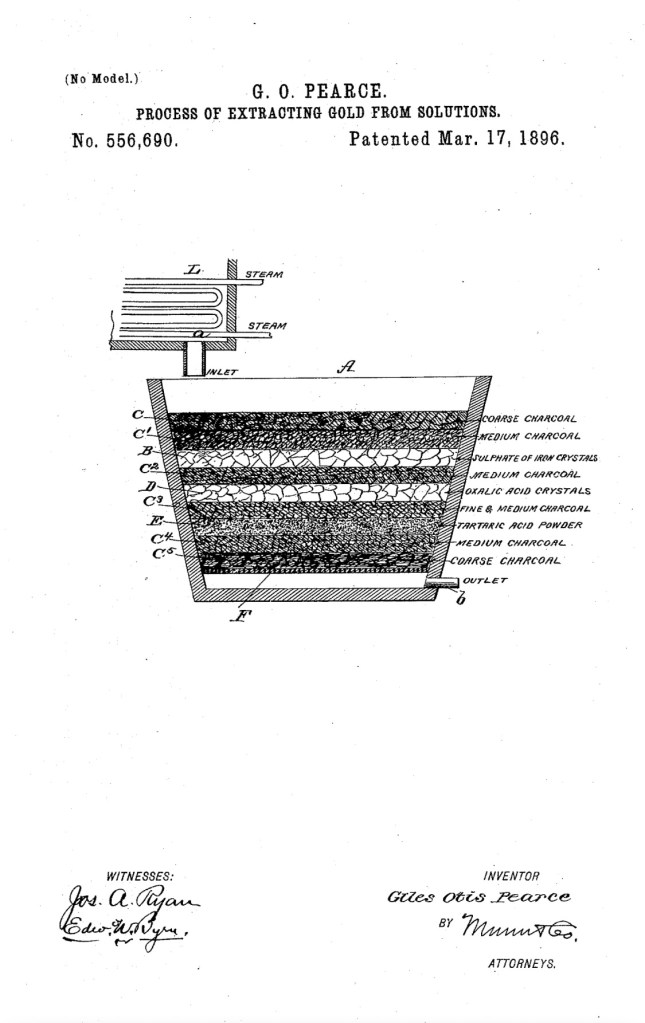

A detailed and lengthy article from the Oceanside Blade explained, in part, how it was supposed to work: “Mr. Pearce is the inventor and patentee of a process for extracting gold from the waters of the ocean, which are said to contain, in solution, four cents of gold to every ton of water. By the use of chemicals the gold is precipitated and caught in a deposit of charcoal in the bottom of a barrel or other receptacle. The cost of elevating the ocean brine into such receptacles has been the chief difficulty in the way of a successful solution of the question. It is believed that the Schuyler wave motor will accomplish the desired result.

“From each barrel, filled and refilled the proper number of times, it is claimed by Mr. Pearce that $153 gold per year can be saved. He also claims that every cubic mile of sea water contains $65,000,000 in gold. It is understood that negotiations are under way whereby the two patents will be consolidated. His patent is controlled by the Carbon Gold Precipitant Company of Colorado.”

While the extraction of gold was questionable, Schuyler’s invention may have been ahead of its time: “A test machine will be put in during the present summer. It is hoped it will prove a success, and that the almost unlimited power of the ocean breakers at our door will be turned to account. If this can be done, electric lights, manufacturing, water galore for irrigation and every other purpose, a railroad up the valley, all will come as a result of the capital that will surely follow the demonstration.”

The city council granted permission to use the wharf for “scientific purposes”, and to “erect such machinery necessary for the purpose of extracting gold from the ocean, such machinery not to interfere with the travel on same.”

Giles Otis Pearce may have been one of the first to perpetuate this ruse and claim he could extract gold from the ocean but he wasn’t the last. In 1898 Prescott Ford Jernegan claimed to have invented what he termed a “Gold Accumulator” that could extract gold from seawater using a process with “specially treated mercury and electricity.” His hoax was exposed and he was sued by investors.

Schuyler’s wave motor seemed to be a legitimate apparatus but its use to extract gold brought expected skepticism. The editor of the Escondido Advocate newspaper challenged the veracity of the editor of the Oceanside Blade to publish such claims: “The article states that Giles Otis, a mining expert, who has patented a process for precipitating the gold in ocean water, was in that city last week consulting with John Schuyler, who has patented a wave motor, and these two will join issue and put in an immense plant at Oceanside. It is estimated that each ton of ocean water contains five cents in gold or $65,000,000 for every cubic mile. It is proposed by the parties interested to handle about a cubic mile of ocean water daily, and with the surplus water power which is as unlimited as the confines of the ocean, a system of electrical power will be put in along the San Luis Rey for pumping plants and the entire country is confidently expected by be submerged under twenty feet of water by the first of October. They then will have electric lights and street railways for Oceanside with all kinds of manufacturing industries to follow. Ed, we take off our hat and unanimously vote you the greatest prosperity liar of the age.”

Giles Otis Pearce was a litigious eccentric. He filed dozens, if not hundreds of lawsuits, including the estate of Theodore Roosevelt. If he lost a suit, he promptly filed an appeal.

Born in 1851 in Muscatine, Iowa, Pearce was well known for his wild claims, and considered a “crank” by locals. He changed, or rather, collected, occupations including printer, journalist, assayer, chemist, smelter, and lawyer. He served as a private in the Ohio Calvary from 1872 to 1873.

In 1885 Pearce ran for governor for the territory of New Mexico. After President Grover Cleveland appointed someone else to that position, Pearce sued the government. In 1886 he claimed to be under the influence of spirits, threatening the lives of family members. He was placed in an asylum in Endicott, Nebraska, but escaped. In 1890 he was “judged insane but harmless” and allowed to retain his freedom as long as he “behaved” himself.

After moving to Colorado, he disputed the recorded height of Pike’s Peak and said that he had determined the actual altitude, which upset and angered locals. He then claimed to have the capital and means of driving a 17 mile tunnel through the Rocky Mountains, at an expense of $25 million. He did not win over any support for his claims and the residents of Cripple Creek asked him to leave. After leaving Colorado, Pearce made his way to Yuma, Arizona, San Diego and then to Oceanside.

But before Schuyler’s wave motor and Pearce’s gold extraction device could be put to the test, the pier needed to be extended and that would take another year. It was extended one hundred feet into the Pacific but it was far too short to provide “boating facilities.”

In June of 1898 work on the pier continued and the Blade provided this update: “Things are progressing nicely toward finishing the wharf. The money will be available in a few days and next season will find us provided with good boating facilities. It is suggested that the work of superintending further extensions be placed in experienced hands so that our pier may be a thing of beauty instead of bearing a resemblance to a tortured snake.”

In October of that same year, Schuyler had placed his wave motor on the pier and demonstrated that it would in fact pump water “in sufficient quantities to warrant the putting in as an experiment of a Pearce filter for extracting gold from sea water.”

However, little to mention of gold extraction and/or Giles Otis Pearce was made after that time. The experiment was apparently abandoned.

Pearce left for Los Angeles where he married (for a second time) to a 21-year-old woman (he was 49) in June of 1900. Just months later during a contentious divorce he declared publicly that his wife was insane. He tied her up to keep her from leaving him and then made a complaint to law enforcement that his wife’s aunt was trying to have him killed and insisted that she be arrested. Pearce died in 1924 at the age of 73 in the National Soldiers Home in Los Angeles. His hometown newspaper noted his passing and his “eventful life.”

On November 9, 1898, the board of city trustees met in adjourned session, where it was reported that the wave motor on the wharf was “straining that structure and Trustees Paden and Nicholas were appointed a committee to investigate and report on same.”

A year later the pier had still not been extended. In November of 1899 the Oceanside Blade published a plea to citizens to step up or see the second pier face the same demise as the first: “While the necessity is apparent of finishing our wharf in a substantial manner and extending it enough to make a good boat landing, the necessary lucre is not in sight as yet. We should be glad to publish suggestions or communications from any of our citizens, on the subject. Something should be done or we will wake up some fine morning after a storm and find the present wharf not present, so to speak. In other words washed away…defunct.”

The Pacific Ocean continued its assault on Oceanside’s little iron wharf until a new pier was built in 1903.

Nice article. Can you help me with more information on Giles Otis Pearce and his sea-gold-project? Could you kindly send me newspaper articles/links on him?

LikeLike

You can search for articles using this database https://cdnc.ucr.edu/

LikeLike