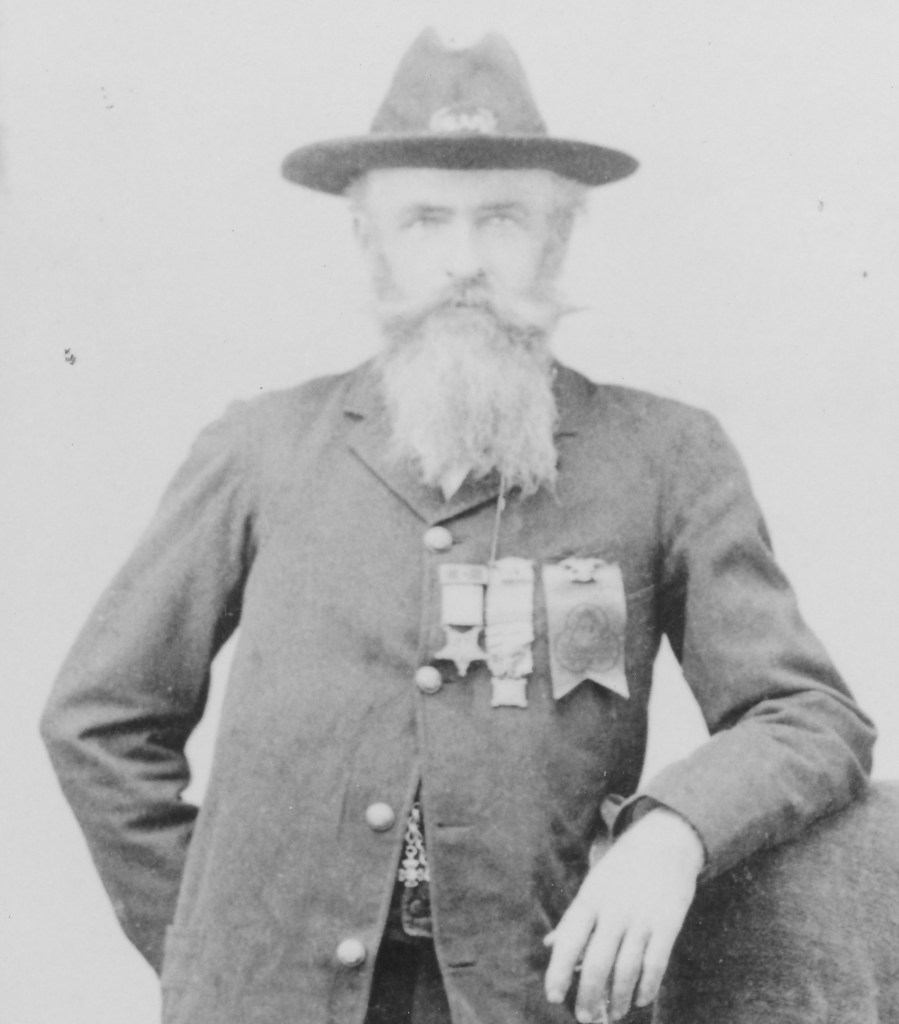

Just two years after Oceanside was established in 1883, Magnus Tait arrived here from Lawrence, Kansas. He purchased considerable property from Oceanside Founder Andrew Jackson Myers and Tait Street is named after him. His youngest son, Magnus Cooley Tait, followed his father and became the manager of the Oceanside water works, bringing water into town by wagon.

The elder Magnus Tait was born in 1837 in Scotland, coming to America with his parents as a child. The family settled in Joliet, Illinois. In 1858 Magnus Tait married Antoinette Cooley and fathered four children.

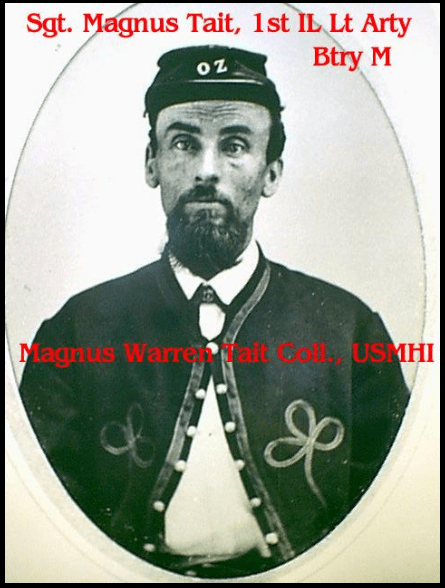

In 1862 the Scotsman enlisted in the Union Army and was assigned to the 1st Illinois Light Artillery. In 1864 his battalion went from Tennessee to Georgia to fight against the confederacy during the Civil War. He was captured and taken prisoner, in Camp Lawton, Blackshear and the infamous Andersonville Prison Camps, enduring with thousands of other Union soldiers, starvation, scurvy and torture. Near death he weighed just 67 pounds.

Magnus Tait wrote about his hellish experience, (note: insensitive language) published in a small booklet, which was then published in the South Oceanside Diamond newspaper in 1888 with the following headline:

IN LIVING HELLS!

A True Story of Rebel Prison Life!

By Magnus Tait,

Battery M 1st Illinois Light Artillery

In writing an account of my prison life, I may err some in dates, as it is all from memory, having kept no regular Diary, and most of us felt that if we survived the war, we would want to forget all as soon as we could; “but all of which I saw, and part of which I was.”

I enlisted in Battery M, First Regiment of Illinois Light Artillery, at Camp Douglas, Chicago, Illinois, on August 4th, 1862, and was mustered in the United States service on the 12th. Was promoted to Sergeant of No. 6 Gun, and left for the seat of war, Sept. 27.

I will not follow our Battery from that time through all the different battles and skirmishes in which it was engaged, but leave for better hands to write its history. Since the war, I have heard Gens. Sherman and Sheridan, and Col. Bridges (who commanded the Artillery of the 4th Corps.) praise its fighting qualities.

After leaving Cleveland, Tenn., on the Atlanta campaign, and being engaged for about one hundred days–that is, some part of the day or night–the left section of the Battery was “turned over” as worn out and not considered safe for further use; so, at Marrieta, Ga., on June 30, 1864, No’s 5 and 6 Guns were “turned over”, most of the horses condemned and the men distributed among the other four gun squads. I was then put on detached duty, sometimes as Orderly for Capt. Spencer of our Battery, making trips back to our wagon train, returning with forage for the horses, hard tack and ammunition, and then escorting refugees back through the lines, and at the same time had orders from one of Gen. Stanley’s Staff to do some detective work.

At that time I had the only Chicago horse left in our Battery–the one I rode out of Chicago. He knew the drill as well as I did. I never had to go around a log or throw down a fence on the march. At two different times, I owed my life to this. Once in Georgia, I was alone, the rebels turned loose on me, after firing a volley, they started after me on the run. After a two mile run, I discovered a squad of “gray coats” in the road ahead, waiting for me to run into them. I turned, leaped the fence and headed for camp, and cleared three fences before I again struck the road. His name was “Festus”. When I was captured and a “Johnnie” rode him off–or rather, tried to–he turned his head and called, as much as to say–“Good-bye”. The brine came to my eyes–I could not help it–the last time I ever saw him. He was wounded twice–one only a scratch, at New Hope Church. At Resaca, he had a ball in his leg below the knee. I bound my handkerchief around it and after we got to camp, cut the ball out. “Noble Festus”, may his ashes rest in peace! and, if intelligence live hereafter, may we meet again.

ATLANTA, Aug. 25, 1864;–Today, the 4th Corps, with Sherman, swung around Atlanta. All extra baggage was left behind. Battery M had about four loads and a lot of stuff for Col. Bridges. I was detailed by Captain Spencer to remain in charge of it. His orders were verbal–about like this “Sergeant, you remain here and take charge of the ‘plunder’ until the wagons return for it, then you loan up and follow as quick as you can.” He probably did not then know the magnitude of that “flank movement,” as he called it; for, before the Battery had got out of sight, one of Gen. Stanley’s Staff rode up and asked me what I was going to do with those supplies and what were my orders. I told him my orders were from my Captain for me to remain there until the wagons returned for it. He smiled and said he did not advise to disobey orders, but that the pickets then in my front would be removed at 12 o’clock that night, and thought it would be safe after that; but the pickets were withdrawn between 9 and 10, and all firing ceased at dark, and I was taken in somewhere near midnight, by the 58th North Carolina Cavalry. They came from toward our lines, and I supposed they were our men until they sang out–“Surrender, you–Yank.” Next morning I was taken to Atlanta, before a General Pember or Penter, and was there questioned for half an hour, about Sherman and his army. He thought Sherman was on the back track towards Nashville, and that our army was out of grub, on account of Wheeler’s cutting the railroad so that we could not get supplies. I said “Yes,” to all that, and in twenty-four hours, Sherman was in Atlanta. This officer was an Englishman. He said that Sherman was worse than any pirate and his men were robbers. He said, “Your army has been firing into the city, with our women and children here, but have not killed anything but a wench and a mule, but this is not Sherman’s fault.” I took good notice, as I passed through, that we had knocked many a hole in the buildings: nearly every one that did not have a cellar, had a hole dug back of the house, covered with pine logs and dirt, to crawl into when we would open with our batteries. The night before the movement, our four guns fired one hundred (100) rounds, each.

On the morning of Aug. 6th., we started for Macon. Remained a few hours at East Point, where there were about 30 more “Yanks” brought in. I could see that the “rebs” were very anxious to get us off. If they had remained there a few hours longer, we would have been recaptured, as Sherman’s cavalry were up to the track next day.

Reached Macon 27th. Were put in a large building that looked like a warehouse. The guards told us that it had held “heaps of you-uns, before.” Here I was made to take off a good pair of artillery boots, almost new, and was given in exchange an old worthless pair of shoes, by a rebel officer. One of my guards next took my jacket. It was new–had drawn it only the week before and had not had time to put on my chevrons. They gave me an old blouse, taken as they said, from a dead “Yank”. The natives, all along the road, were very abusive and at some stations, the women were the worst. We would have fared badly had it not been for our guards.

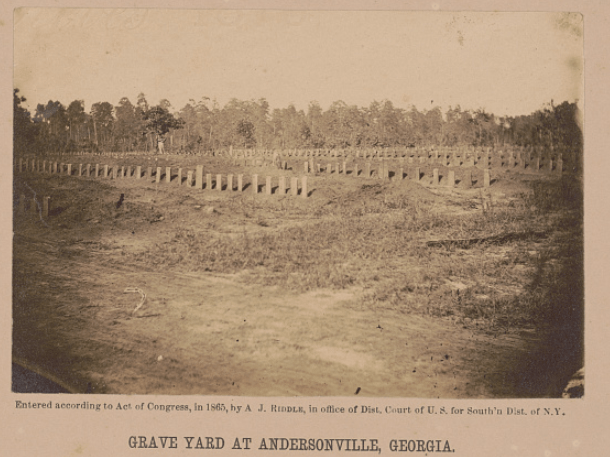

Arrived at Andersonville, Aug. 29th., I think. Was marched in front of old Wirz’s headquarters–that infernal devil that was hung for obeying Jeff. Davis’ orders, and the Arch Traitor allowed to go free and is living today, (Sept. 1888,) and if he wished, could be drawing his $16 pension per month from the government he tried so hard to destroy, while thousands of old soldiers who gave the best three years of their lives to serve and maintain the Government, and now in poor-houses, throughout the land–many without pensions. But I have got off the track.

There were about thirty of us in the squad. We all stood in single file. Wirz ordered a “reb” to search “every Cott tam Yank.” Those who showed any resistance were stripped. Money, watches, pocket knives, pictures of wives, children or other dear ones, were taken. One soldier had an ambrotype of his wife or mother, I did not learn which, as he was about half-way down the row and I was at the head. He tried to retain it which made Wirz so mad he snatched it from him, and threw it on the ground and with his boot-heel rent it in pieces. The boy made some remark for which he was taken off by two “rebs” and put in the stocks for six hours.

We were then turned into the pen. I will not attempt to describe it, for I could not do it justice; for, as comrade McElroy says in his book on Andersonville, that “would require a Carlyle or a Hugo,” so I would refer the reader to McElroy’s Book. I can vouch for the truthfulness of his statement in the different prisons in which I was confined, and will add that he has not all, for the English language cannot describe it. There had been 35,000 prisoners in there at one time; but at that date, there were reported to be 28,000, and the death-rate over 100 per day. We were piled with questions about Sherman, and if the Confederacy would soon be “played out”, and if there was any news about exchange, and many questions to relieve the minds and bodies that were starving to death by inches.

I wandered along, crossed the swamp near the rebel sutler’s tent and sat down on the ground and began to think what chance there was for me to live in such a place with not a thing to cook or even to eat my rations in, if I had any, except an oyster can a guard gave me in exchange for my tin cup, and an old jack-knife that I had slipped in my shoe with the photograph of my four children. These I kept all through and brought home with me.

While sitting there, I could see the sand alive with “gray-backs,” so I got up and began to hunt for the “hundred” I was put in, but did not find it that night. Another sergeant who belonged to an Iowa regiment, who was turned in with me, and I, lay down on the ground, but not to sleep. We talked about what we had seen in the few hours we had been in. He said, “It does not seem possible that our Government can know or believe that it is one-tenth as bad as this, or it would march an army here at once and release the prisoners. Why if our women in the North, could even take one look in here, they would march down here and turn the ‘boys’ out!” That is the way we talked, until the sentry on the box sang out, “Three o’clock and all is well!” when we closed our eyes.

We did not find our squad next day, in time to draw our rations; but that did not trouble as much then as it did later on. We thought we never could eat wormy peas and a piece of half-baked corn bread. That night about sundown, I was beginning to feel as if I could eat something, if I could get it, so I went down to the “Providence Spring,” as it is now called. It had broken out a few weeks before I came in after a heavy rain. I think the water had dammed up against the stockade and followed along the bottom of a trench that it was set in, five or six feet deep, until it struck some of our tunnels, and then broke through on our side. It was a Godsend to the prisoners, no matter where it came from, and it probably saved thousands of lives that the rebels intended should go by drinking from the swamp that received the filth of 35,000 prisoners.

But to return:–I had taken a drink and filled my can and was returning, when I ran across Geo. Pickle, a comrade of the 100th. Illinois, captured at Chattanooga. We had been school-mates. We were both surprised and I was delighted to find some one in that hell I was acquainted with. I went to his hole in the ground, covered with half a “pup tent”, and there took my first meal in Andersonville. He had some soup made from cow peas, and every pea seemed to have from two to four bugs, and when he handed me some in my can I began to skim off the bugs, he smiled and said that in a few days I would be very glad to take my soup–bugs and all, which proved too true.

In about three weeks, I was taken with bloody flux, and did not expect to recover. Nothing but a determination to live and return, was all that kept most of us alive at that time. I told my Iowa friend (I wish I could recall his name,) to take my photographs and write my wife if he should ever be released. We had nothing over us, but lived in a hole scooped out of the bank. I had half a canteen. He had been watching for a rat he had seen come out of a hole near the cook house, and had made a snare from some horse hair to which he attached a string. Then he put the snare over the hole, and would lie and watch for hours. At last he “fetched him,” and I think he saved my life. I was able to sit up, but could not walk. I think I can taste that rat soup to this day! I soon got so I could walk around once more.

Some may think that swearing does not good. Well perhaps not, in “God’s Country”; but I have seen prisoners so low that they could not stand, who, after damning the rebels for ten minutes, could get up and walk!

Sometimes we would wish to be God for a while, and we should have the rebels suspended over hell, with a knife to cut the rope. This, talking about “something good to eat”, and various plans of escape, and the prospects of being exchanged, were about all our conversation. We wondered why our Government did not exchange us.

Many tunnels were started. Some of them were underway for months. The rebels would find them out by one who was nearly starved, betraying his comrades for the chance of being taken outside and having full rations. We would have killed them, if we could have got hold of them then, but now, when I look back and think it over, I cannot blame them, for in their starved condition, they were not accountable for what they did, when it was for something to eat.

I worked nights for three weeks, in one of those tunnels. We were all sworn to secrecy. Our tools were case and butcher knives, a half canteen and a broken shovel. We would haul the dirt up in bags made of meal sacks, hang them around our necks, and walk around the camp and scatter it as we went. In the morning nothing could be seen. We had dug under two of the stockades, (there were three around the prison,) and were waiting a favorable night to make a break, when it was discovered! Some thought we had been betrayed, but we could never spot the man. Some of the second row of logs of the stockade, began to sink. We had run up too close to them. The “rebs” began to dig, and soon found our hole.

I never tried tunneling after that in Andersonville, for I now began to feel the effects of my prison diet. Scurvy and diarrhea both began on me. One of my legs began to swell. My left foot got to be about twice the ordinary size. My gums were swollen and my teeth were so loose, I could pick every one of the front ones out with my fingers.

The few rags I had on were only kept together by sticks or stings. I never saw, while I was there in any of the prisons, one garment of any kind, issued by thee rebel government. The only way our supply was kept up, was by taking the clothing from the dead, and then we would draw lots for the different pieces. We would tie a string (with something for a tag, attached, giving his name and regiment,) around the neck of the dead. The rebels would throw the dead in the mule wagons like so many slaughtered hogs, and in the same wagons that they brought our rations in. There were some prisoners brought in–a Tennessee regiment, that Wirz stripped almost naked because they were from a Southern State and when I left Andersonville, a great many of them had nothing on but a piece of old blouse or drawers around the waist, like Indians; but unlike them, they had no blankets and no covering at night, but would huddle together like hogs, to keep warm; and in January, that winter, ice formed thicker than window glass, a number of nights; and almost every night, there was white frost.

Every day we would take of every rag we had on, and “esa” as we called it. We would turn our clothes and pick off the “graybacks,” throw them on the ground and then dress. When one became so weakly or negligent that he did not perform this duty every day, you could tell about how long he would live; for it was only a matter of time, if he had any clothes; for it would not take the “graybacks” long to suck out what little blood he had left in him, as the sand that we lay was alive with them.

My leg and foot began to grow some better so I could walk around. I dug some roots out of the swamp that received the filth of the camp, and pounded them up, steeped them in my can, and drank the tea. I did not know or care what they were.

About this time I sold some corn mean beer on commission, for a comrade who had in some way, smuggled in some greenbacks and bought a sack of meal. He would put some in water and let it stand in the sun, then add a little sorghum, and in two weeks it made splendid beer–that is, we thought so. For every four cups I sold, I got a 5 cent greenback or 25 cents “Confed”. I think this sour drink helped my scurvy.

Our men did all the work of burying our dead comrades, and when any were taken out to do that work, they took an oath not to go over two miles from the camp, and they got full rations while out. When I first got in the pen, I found a brother Scot by the name of John B. Walker, a shoemaker. He was taken out to make shoes for Wirz’ wife and daughters. He made them from Yankee boot tops, as leather was $60 to $70 per pound. I sent work by a rebel driver, for Walker to get me out side to help in the cemetery, if possible. In about a week, I was taken out with four others, and sent to the Yankee prisoners’ quarters. I found Walker the man I think I owe my life to. He was from a Pennsylvania regiment. I forget the number. He showed me a pencil sketch of the pen, and at the close of the war, he had it lithographed and sent me a couple of views. I have not heard from him since. The first night out, we all ate too much. If it had not been for our friends, three of the five would soon have been laid in the shallow trenches that we went out to dig for others. I never can forget that night’s eating, for we wanted to eat all the time. It was good corn meal, not coarse stuff, such as was served to us inside. Two were turned back in a few days. I did not do one half my task, but some of my comrades helped me.

The trench was six and a half feet wide and two feet deep. The dead was laid in as close as they could be then a short board was put down at the head of each, with whatever name or regiment that was on the tag pinned on his rags or tied around his neck.

I was out two weeks; but had to be returned inside, as I was too weak to do any work. I saved about three pounds of meal to take back. I made me a shirt from a meal sack, by cutting a hole for my head and one for each arm. I had then been some time without any. I also made a pair of pants from another sack. I took in with me a hickory stick for a walking cane. The shavings that I cut off in making it, served to cook my peas. I have it yet.

While outside, we could hear the chaplains pray every night, asking God to destroy the “Yanks”, and drive the invaders from the South; but not one of them ever came inside or said one word to us about this world or the other–I mean of the Protestant ministers. There was a Catholic priest by the name of Hamilton–a pleasant-spoken man. I think he came from Macon. He would come among the prisoners and would perform the last rite of the church for one who wanted him to; but we could not get one word from him about how things were progressing outside. I asked him one day, to bring a newspaper, but he shook his head–he did not trouble himself about such matters. One day a little dog followed him inside the stockade. Whether it was his or some “reb’s”, we never knew. I followed him for nearly an hour, to catch the dog; but could not make it. I think he mistrusted, for the dog never came again. O, what a feast we would have had, if I had caught that dog! I could have cut him up and sold him for 50 cts. greenback, and his hide would have been a fortune!

To quote a few notes taken at the time–“Andersonville, Sept. 8th. This morning, 2,000 of us were taken out and put on board the cars, 80 in a car. The “rebs” told us we were going to be exchanged–300 having gone the day before. Were two days and nights on the cars. Were not allowed to get out for anything. The guards would give us but little water. Arrived at Savannah on 10th. Entered the city on Liberty street. Lay in the cars an hour, as the pen was not ready. We were surrounded by the Stay-at-home guards and the belles of the city. Some of the remarks of both, made us bite our lips; but we had to take it.

We were then unloaded and marched up Washington street past a large prison, to the outskirts of the city and halted, as the fence was not quite finished. It was a large enclosure somewhat like fairgrounds at the North–posts and strings with twelve foot boards nailed on the inside. As we lay there on the grass, what a contrast to the lice and filth we had left!

A few minutes after we were halted, a number of women with servants, carrying large baskets filled with victuals, covered with white clothes, asked permission to distribute them among the prisoners; but a rebel officer near me, ordered them to leave the grounds at once, or he would have them all arrested. O! what a tempting sight were those white covered baskets! They were so near the squad I was in so that we could smell the stuff, and I think I can smell it yet, after all these many long years! Remember, we had had nothing for the trip but one “hard-tack” and whatever we had on hand to start with.

We were turned inside Sept. 11th., the pen was so crowded that we could hardly lie down. They had put 1,000 more in that they had calculated on. They had been sent to some pen in South Carolina; but the “Yanks” had burned a bridge, so they were returned and put in there. We drew rations that day–the best we had had in the Confederacy, and more of them; meal–1/2 lb., bacon one inch square, rice–1 pint, salt–one tablespoonful and wood to cook with–something we never received at Andersonville, although we were there in midst of a pine forest. Every other day, we would get a small piece of beef instead of bacon. This is about what our rations were, while we were at Savannah. About once a week, they would drive in the pen with a barrel of poor molasses. Some of the boys called it Sorghum. Each one would get a small allowance. It was fine for the scurvy. Some would drink it and some would make beer with it and a little rice water.

When I was turned in, I looked around to see if there were any one I knew, but could find none. I sat down by the gate and wondered how long before we could see God’s country. I had now an old quilt, a tin plate, half-pint cup, a spoon I had made out of a piece of tin, and a 50 cent greenback I had made peddling tobacco. The quilt, cup and plate, I got from a comrade who was taken out for exchange.

While sitting there, three members of the 5th Indiana Cavalry, came along. Their names were Nathan Williams, Thompson Alexander and John Doughety. We formed a squad by ourselves. They had one blanket and one half “put tent”. I took my 50 cents and bought some small poles. We took the tent and blanket and made a cover to keep off the sun. By lying close together and “spooning”, we could be covered at night with my quilt.

That night I dug out under the fence, with my half canteen. The ground was sand, and the boards were down only a few inches. The night was very dark. I went right into the city, for we had heard there were many Union people in Savannah. I thought it I could only strike one of them and could be secreted until Sherman arrived, I would be all right.

When I had got well down into the town, had crossed two railroad tracks, and was wishing I could meet some darkey, (for I knew he would direct me O.K.), when I ran right into two men who took hold of me and asked me who I was and where I was going. I did not answer as quickly as I ought, and when I did, I gave myself away. One was a rebel corporal. He turned me over to the other who was a citizen. He took me to his house and locked me up in his smoke-house. Next morning I was given a corn pone and a bowl of milk–the first I had in the Confederacy. I was then taken down to the pend and hurried in without any punishment, as the lieutenant in charge said it was his business to hold us, and our to get away if we could.

The pen was terribly crowded. They had put in one-third more than was intended. The citizens were afraid we would breed some contagious disease. The mayor and others told the officer in charge, that if it were not enlarged or some of us sent away, they would tear the pen down some night. They did not care so much for our comfort as for their own health. They then extended the pen and also dug a ditch on the inside, a short distance from the fence, which stopped all further tunneling under it. The ditch also served as a dead line.

One day, in the afternoon, a darky drove in with his four-mule team and the barrel of “long-sweetening”, as the boys called it. It was a very warm day, and the jolting of the wagon had stirred it up, and when it was rolled off, it struck on the chimb, and the head blew out and scattered about one-half on the boys who stood around. In the confusion, I crawled under the wagon and got up on the hounds. When I had got in about as small space as possible, I looked around, and there lay another Yank on the front hounds! We did not have long to wait. The darky soon got up on the wheel-mule, took up his rope line and drove out the gate. We went about two miles, to the edge of the timber to a wood camp. I told my chum to lie quiet until dark, and we would then slip the city; but as soon as the driver unhitched and turned out his mules, he called to some other darky to come and help him “off wid de box an’ put on de wood-rack” to haul a load of wood to the prison next morning. When they lifted the box, we scared them so badly they let it drop! The white boss who was standing near, took charge of us, put us in one of the board shanties, gave us a good supper and breakfast and said he would have to turn us in, as there were two other white men there who saw us. This old man appeared to be for the Union, as much as he dared be. He was seventy-five years old, and said the Confederacy has about gone to h–l and he was glad of it–that he had lost two sons fighting for the d—d slave-holders.

We rode into the prison, next morning, under guard of one of the white men, armed with a fine English breech-loading shotgun. We escaped punishment again but every wagon that went out after that was searched inside and out. I never knew that comrade’s name, but he belong to an Iowa regiment, and if this should ever reach him, I wish he would write me at Los Gatos, Cal.

Savannah, Ga., Oct. 12th. This morning the rebels told us we were going to be exchanged–the old story, when they wanted to run us to some new place or “bull-pen”, as we called it. We were put in boxcars, eighty to a car, and run to Millen, Ga., called Camp Lawton. It is a new camp, with plenty of stump-wood. The trees had all been chopped down and hauled away. A stream of water runs by it like Andersonville, but no swamp. As we were among the first arrivals, we had plenty of wood. Rations not as good as Savannah-less meal and more cow peas. The man who donated this land for our use, was a rebel captain. His wife said they owned 900 acres of land there, and she hoped they would catch enough dirty Yanks to cover their entire tract. (That man since represented this government in Austria–one of Cleveland’s appointments.)

October 25th. This morning Thompson Alexander died. We drew lots for his clothes. His boots fell to me. I cut the tops off and traded them to a rebel guard for $5.00 worth of tobacco which I cut up in small pieces, half an inch wide, and peddled them around camp–sold them for 5 cts. greenbacks, or 25 cts. “Confed.” or one ration. I limited myself to three pipes per day.

Nov. 8th. This morning the rebel captain came in and told us they were voting for Lincoln and McClellan, in the North, and he wanted the pen to vote, to see how we stood. I was appointed one of the judges. The Johnnies came in to see that we had fair play. We used black beans for Old Abe and white ones for McClellan. When we counted up, we had polled 4,500 for Old Abe. At that time there were not over 6,000 in the pen. The vote made the rebels made. The keeper said he hoped that we would lay there until the maggots carried us out of the stockade.

In about a week or ten days an order came to exchange 700 prisoners. We never knew what the order from our Government was, but we heard it was to take 700 sick. But they took very few sick men, unless they had a watch or $50 in greenbacks; or, if they were Masons they were O.K. A $50 greenback, a gold watch, or even a silver one, was all that was needed to again see God’s country and Home!

About the 20th of November, several rebel officers came into camp and told us our Government had forsaken us and was content to let us lie in prison and rot–that England and France were about to recognize the Confederacy, and that the best we could do was to enlist in the Southern army. We would get good clothes and plenty to eat and the same pay as their soldiers. A few went out, but I never knew how many. I know that several were from New York city–mostly Irishmen who had been cursing Old Abe and praising McClellan, as much as they dared in the pen. The next day they called out every foreigner and wanted every man who was not born in the United States, to go outside the stockade. I supposed we were then going to be exchanged; but after drawing us up in line and separating the artillery, cavalry and infantry–each by themselves, they made about the same talk as the day before. I was offered a lieutenant’s commission in a battery; if I would join the Confederacy and take the oath; but I told them NO! I would do anything outside, that I was able to do, that did not require me to take an oath against my country–that I would try the pen awhile longer. There were a few who availed themselves of this way to get out–some few in good faith, hoping to get a chance to desert to our lines; but the most who went were men who hated the “d—d Nagur.” They said all the war was got up for was to free them. They were going on the other side.

Toward the last of November, we were ordered out and hurried into box cars–70 to 80 in a car, and given two hard-tack. The most of us took what cooking utensils we had along, although the guards told us we were going to be exchanged; but they had lied so often to us that we could not believe them. We heard rumors that Sherman was getting too close to Camp Lawton. We were run to Savannah, then changed cars and went on the Gulf road. We were five days going 80 miles. All we had to eat on this journey, was the two hard-tack and a pint of shelled corn. A great many died, when they came to eat the dry, hard corn. The engine was about played-out and if it had not been for a Yank who helped repair it, they would probably have had to abandon it. We arrived at Blackshear, Ga., Dec. 3d. 1864, in the night, and marched into an open field. It was the coldest night I ever felt, while a prisoner. Ice froze two inches thick. We had only two log fires for all 4,000 men. The strong kept away the weak ones from it. I tried it, but was shoved away, and I wandered around trying to keep warm or from freezing. I think I suffered more that night than nay other, while a prisoner–at least, I remembered it with greater horror than any other night! In the morning stiffened bodies lay around in all directions! I remember one place close to the track, where five men lay dead, with a thin, old blanket over them. I never knew, nor have I ever heard, whether these bodies have been removed, or if there is anything to mark their resting place. We never could get the right count; but we heard before we left, they had buried 300 Yanks, or, as the guards said: “We have 300 less to guard.” Others said there were only hundred and sixty.

We remained at Blackshear a few days. It was only a railroad station, in a heavy pine woods. A few long-haired natives–very old and slab-sided women–came to see us. They looked as if they thought we were some wild animals they had never seen before. I heard one woman say she had not thought the Yanks were so black, and another said we did not have thick lips and curly hair like their darkies. We were just as black as any Southern field hand, caused by the pine smoke from what little fire we did have and not having seen any soap from the time we went in. One thing that looked strange to us was–all the young women (and the old ones, too,) seemed to be as straight as the pine trees that surround them. Bosoms or busts they did not have, nor were there any visible, outward signs of any; and even the negro wenches we saw there, were not burdened in that way. Some of the boys, while we were waiting at the platform for the cars to be backed up, were making observations about how the children were raised, and most of them tow-headed, when one Yank said the country was so d—d poor that the women could not give milk to their children, and they had to be raised on cow’s milk. Some one in the crowd heard it and told the rebel captain. He called the man out and asked if he made those remarks. He acknowledged that he did, and told him what remarks they had been making about us. It pleased the captain so much that he told the guard to “give that Yank an extra hard-tack.” He said that the men who built that railroad through such a country ought to be hung; and if he remained there a few days longer, he would hunt around and kill all the cows and thereby cut off their supply, so they would have to move out, if they raised any more children. That gave us the laugh, and we moved into the cars, and the natives took an extra dip of snuff!

About Dec. 6th. or 7th., orders came to pull out, as Sherman was at Savannah; so we were again piled into cars, and run to Thomasville, the end of the Gulf R.R. We were fifty-two hours making the trip, with an old, asthmatic engine, and four, small hard-tack to eat, for the entire journey. That was all that was issued to us by the rebs; but there were a few who had some money, and they could some sweet potatoes and now and then, a pie which was sure death, unless the Yank who ate it, was able to walk around a few hours after. I got some sweet potatoes twice, on the trip. I traded some Yankee buttons that I had cut from the jacket of a soldier who died in the car that I was in, which I did if I could get to them first or before the rebel guards came around. The were just as good as greenbacks.

My teeth and gums were so bad with scurvy that I could not use them. I had a piece of hoop iron with one edge sharpened some on a stone. This I would use as a knife to scrape the potatoes. I began to improve from the first potato I got hold of.

Thomasville is quite a town, on a rise of ground, and is surrounded by swamps–the county seat of Thomas County–was reported by the natives where we were there, to have 2,500 inhabitants.

We were turned in the woods, and a strong guard placed. Several of the boys got away. Quite a number returned and gave themselves up. They told me they waded in swamps waist deep. They did not think it of use to try to escape, as the turnpike and railroad brides were both guarded but I heard of a few who did reach our gun-boats after terrible suffering.

Our rations were mostly yams–very little bread, some rice and pure water: so most of the camp began to pick up. A few of the very weak ones dropped away very quickly.

About Dec. 10th., the rebel sergeant in charge of the rebel guard, (who was a Scotchman from Canada, and as all the men in his department had to enlist, he enlisted in Home Guards; but was a good Union man) came in and he and I had a few talks on the sly, from which I inferred that the Confederacy was about on its last legs. One morning, he came to me and wanted to know if I could repair a piano. If I could, I would be taken outside and up town, and have plenty to eat. I told him I used to make pianos, in the North; but was afraid I could tune one then, as I had been out of practice so long.

Next morning, an order came from the captain, that I should go to headquarters and take an oath not to go two miles from the city, and must report every morning–the sergeant agreeing to stand for me. He told the captain that our fathers were acquainted with each other, in Canada. The sergeant told me that the furniture which I was to repair, belonged to one of the nobbiest families in town. I am sorry that I cannot recall his name; but the man was a colonel of a Georgia regiment, then in front of Richmond, and had charge of a brigade. I looked down at my baggy pants that I had cut and made myself, from meal sacks, and said I did not look presentable to go in a lady’s parlor; so he took me up to his quarters, and there, by the aid of soft soap, I did manage to take off most of the black that had been there from the time I first struck Andersonville. It was the first wash with soap of any kind, in the Confederacy. I had thrown away my old shoes that I had tied on my feet with strings, and had taken a very good pair from a dead comrade, in the cars, and I had just completed a shirt and a pair of pants, with very wide legs, from meal sacks. The sergeant cut my hair as close as shears could do it, and he gave me an old hat and jacket, and I was fixed! I lay around his tent that day, and that evening, went down to headquarters to report. Some of my old bunkmates did not know me. They thought I would not live long, I looked so white! I told them about soft soap, and smuggled them in some peanuts which I got from a New York man–an engineer on the road–with a promise of more and an invitation to go to his house.

The next morning I went to Mrs. Col. _____’s house with the sergeant, and was introduced as “Captain Tait, of the Yankee Army,” and was to remain there as long as she had work for me to do. They owned sixty negroes, but most of the able-bodied men were at the front, working on fortifications, or had run away. The negro quarters were full–or seemed so to me–of young ones, from babies up to fourteen. They were of all colors, from very black to very light complexions.

One of the casters had come off a leg of the piano, the rack that held the music was broken, some drawers in a bureau needed fixing, the runners had become loose, and the dining table needed some screws. Well, glue was one thing I wanted. She did not think there was any nearer than Savannah. She was very kind, and was surprised at my weak and emaciated condition–asked me all manner of questions. I told her if she thought I was thin, she ought to see some of those in prison. She said it was a shame to treat the prisoners so, when the Yankee government gave their prisoners so much to eat. She told me she had a brother captured in Shiloh, who was taken to one of the Northern prisons. He was exchanged and went home, and could not say too much in praise of the amount and quality of food we issued to the rebels.

It was there that I first beheld myself in a glass. To tell the truth, I did not know myself! If my photograph had been taken without my knowledge, and shown me, I should have asked who it was.

I told the lady that if I had some glue and tools, I could fix her furniture. She spoke to a servant and gave her a bunch of keys. In a few minutes she came in with a tray on which was piece of gingerbread and a glass of wine. She told me to take it–she knew it would help me, I looked so weakly. Now, this time I had made up my mind not to eat or drink too much, as I did at Andersonville. The wine, she said, was some that had run the blockade at Savannah, before our gun-boats got so thick. I did not know the name of it. I drank it. She sent out for an old darkey who looked to be a hundred years old. She told him to take me out to the carpenter’s shop, and see if I could find any tools, and to obey my orders, while I was at the house. I went to the shop. It was at one end of the negro quarters. The darky told me he did not think there was anything in the shop but a few old, broken tools, as Jeff. Davis had sent for their carpenter to repair the railroad, and he had taken all the tools.

I had just reached the shop. He opened the door–all I could see was a work bench. I remember taking hold of it as it came swinging around! and lay down on it. Imported wine was too much for me! when I awoke, it was afternoon, and I felt rested. The darky had closed the door to keep the young “trash” from crowding around the shop to get a peep at a real, live “Yank”. I told him to tell his mistress that I could not find any tools around the plantation; that I would go down to the round-house of the railroad and see if I could find some and be up next day. I took a back street to camp, to avoid being stared at by the natives. When I had got half way back, a young lieutenant, who was home on furlough, came up and told me he would arrest me and take me back to camp, as someone had seen me come out of the negro quarters. So I marched down and that young cub preferred those charges. I thought now that I had got myself into a scrape. I waited there about an hour, until the captain came. I told my story of how I went to the quarters. He wrote a note and sent an orderly up to the house. I never knew what the note contained, nor what answer came from the colonel’s wife, but I was released when he read it. He then gave me a pass that read something like this: “TO ALL WHOM IT MAY CONCERN,–Know ye, that Sergeant Tait, Yankee prisoner, is allowed to go anywhere within two miles of the city. He is to report at these headquarters every evening. Captain, C.S.A.

Next morning I went to the little repair shop and found my New York friend. I there got some prepared glue made in London, and some tools–a wood-saw, a file and a gimlet, for Mrs. “F.” as I will call her had brought half a dozen silver-plated knives and forks without handles, and wanted to know if I could put wooden handles on them. She seemed to think a “Yank” could do almost everything. So next morning I went to work, and in a week, had Mrs. F. well fixed up, considering the tools and material I had to work with. Every day, at dinner, when she was alone, I dined with her and the family. My breakfast and supper, I took in the kitchen; alone, waited on by one of the house-servants. The dinners consisted of milk, corn bread, bacon, and yams. She had had very little to eat for six months.

I was then invited to the New York man’s house, to dinner. He and his wife were both Union people, caught South when the war broke out. How anxious the wife was to return to her people! She gave me half a bushel of peanuts and I took them to camp.

I was afraid that I would then be again turned in; but about Dec. 20th, a carpenter by the name of Wood, from one of the New England States, came into camp and wanted to get some carpenters to out to work. He had gone South a few years before the war, and was even more bitter against the abolitionists, than the men were who owned slaves. He offered to give the carpenters good quarters and plenty to eat, and the oath we had to take was similar to the one I had taken. Nathan Williams, John Dougherty, I and some others whose names I cannot now remember, took the oath. [A few years ago, I had a letter from Comrade Dougherty who was then living in his native State, Indiana.]

We were to build works for slaughtering hogs. We had about 40 darkies to help us. They did all the heavy work, as we were not able to use an axe. We put posts in the ground about two feet, had them stick up seven feet and then pinned 2 x 10 pieces on them, flatwise. Then, every four feet, we put in a stout peg to hand the hog on. We put up several of these about ten feet apart, enough to hang up 200 hogs.

We had just got ready to slaughter, when word came that we were too near Sherman. An order came to drive the hogs to Oglethorpe 40 miles south of Macon. Mr. Wood and the “Yanks”, and negro cooks, started for Albany, in a wagon. There we took cars for Oglethorpe, a small town on the Southwestern R.R. There we erected the same arrangements for slaughtering, as we had made at Thomasville. We had good quarters in an old warehouse, where we found about 400 Bibles that were sent down from Boston before the war, to be distributed to the heathen. I gobbled one, and have it in my house now.

We slaughtered about 800 hogs, dry-salted the meat, and rendered the lard. We had plenty of fresh meat and corn meal, but no vegetables. Still, we could hardly do half a day’s work in a day. The scurvy now began to appear, and the diarrhea that seemed to ease up somewhat when we first got out and received full rations, now came back worse than ever.

There I saw the first slave woman stripped and whipped until the blood ran down her back. She was a house servant–an octoroon, eighteen or twenty years old. She was accused of stealing a turkey. Her hands were tied to a limb of a tree, above her head. Her feet were also tied. An old man did the whipping. The yard was full of white children and the rest of the slaves that I suppose, belonged to the place. He gave her twenty lashes on the back. She pleaded with her mistress to spare her, as she said she was innocent; but her mistress told her to confess and tell where the turkey had gone, and told the old devil to give her a dozen more. Before he got through her clothes fell from around her waist, to the ground. She appeared to swoon and hung by the rope that held her hands, stark naked, before the crowd. The slave women took her down and carried into one of the cabins. They did not know that a couple of Yanks were looking at them through cracks in the fence! About a week after, one of the darkies in our gang, told me he knew the negro that took that gobbler, and the girl knew nothing about it. It was over a week before we saw the girl out again.

Rumors began to come that “Sherman was raising h–l through Georgia.” That is the way our boss put it.

There were a few Union men there, but we could only converse with them after dark. They were mostly old men who had always voted the Whig ticket. I want to state here, that I never ran across a man in the Slave States, either while a prisoner or soldiering, who was a Union man and Democrat or had voted with that party; but every Union man had been a Whig and then was with the Republican party. Major Bacon, the man who had control of the whole business, was a very bitter rebel. He was quite old and had been in the Mexican War. He owned several slaves, but most of them had run into the Yankee lines. We said among ourselves, that we were making this bacon for “Uncle Billy” Sherman; and sure enough, the Union Calvary got every pound, but the live Bacon got away.

About the 15th. of February, orders came to stop slaughtering hogs, as Sherman’s cavalry was too near, all “pa-roled” Yanks were ordered in. We were told that we were to be taken back to Andersonville and there paroled; but we had been lied to so much, we did not and could not believe it. We three talked much about making a break for our lines. We had no means of knowing how close we were to them. Had we known, at that time, that our cavalry was so near, we could have made a break and got to them in a few days. We had about made up our minds to make the trail, when I broached the subject to Mr. Wood. I told him plainly that as he had used us like men, we would not try, while we were in his charge. We gave him our word that, while he had control, we would be on hand; but that the night that he might turn us over and get his receipt, we thought of taking “French leave.” He advised me, on his word as a Northern man, that the Confederacy was on its last legs and could last but a few months longer, and he thought the quickest orad home, was to go ahead and be turned over; and; sure enough, it went to h–l in a few months after.

We were taken to Albany and there met the remainder from Thomasville–between three and four thousand–I do not remember the number.

We marched across Flint river, over a covered bridge. When at the middle of the covered part, we met a darky with a mule team and a wagon loaded with ear corn, coming across. The rebel guards ahead, made him haul up along one side and they went on. By the time one third of the Yanks had passed, he did not have one ear of corn left. Some of them got two, three and four ears. I go two. They came very handy before we got to our lines, but I felt sorry for the poor darky. We wanted him to leave the team and go with us.

We went by rail to Montgomery and Selma, and then to Meridian, Miss. There we remained a few days, as the rest of the way to Vicksburg was to be made on foot.

My left leg was swollen to twice its natural size with the scurvy, and the diarrhea had been my greatest trouble since I left Andersonville.

Now, from there to the last day before we reached Black River, I do not remember anything. It is all a blank to me. All I know is what was told me by comrades who helped me along. I should like to know their names. One was a sergeant in the 5th or 8th Iowa.

We were in charge of a rebel major. It had been raining for several days, and we were the most deplorable-looking beings imaginable–scantily clothed, and what we had were rags. We crossed Black River on pontoons, about four miles from Vicksburg, I think, and then took the cars for some point near town.

I shall not try to describe the scene when we first saw the Old Flag floating over Vicksburg! We had at last got sight of “God’s Country”!

Quite a number gave one cheer for that old flag and dropped down dead. The excitement of being exchanged and getting home, had nerved them up to this time; but the emotional feelings were too much for them in their weak and starved condition. As we marched or were carried, up the bank to the top of the hill where we were camped, we were served with coffee and whiskey, by colored soldiers who stood on each side. Some were so weak that a cup of coffee made them drunk!

We were then taken to McPherson Hospital, where our rags and “graybacks” were exchanged for a new suit of blue, but it took more than one scrubbing to get the black of prison-life, washed out.

We were put in wards according to the States we were from. Each State had agents from the Sanitary Commission, sent down with all kinds of delicacies. The one from Illinois, was a Miss Lovejoy, a kind, loving young lady who never seemed to tire of ministering to our wants; for she was with us late at night and the first one we would see in the morning.

The second morning, several of us were weighted by one of the sergeants. My weight was 67 1/2 pounds, without hat or boots. We were told that twenty were to be weighed and their weights sent to Washington, as evidence against Wirz; but I never knew whether they were sent for that purpose or to satisfy the scientific as to how poor and thin a man could get and live.

With all the kind treatment we received, a great many died. Some, when they got able to walk around, if no one watched them, would eat too much. They were like children. The day I got so I could walk outside with a crutch and cane, I could not go far. I sat down under a pine tree, or rather a stump that a cannon ball from one side or the other, had taken the top off about thirty feet from the ground, during the siege. Close to me lay a soldier, rolled up in his blanket–I supposed, asleep. Soon a couple of guards came along and pulled the blanket off his head, when he jumped up and gave a yell, and tried to run but fell. Under his blanket he had several loaves of bread, tin cups, canteens and tin plates! He had recovered so he could walk around, still he was afraid the rations would be short, and he told the guard it would soon be as bad as Andersonville, and he would have some to start with! That afternoon, he went into a tent where some colored soldiers stayed and ate all he could and carried off all that was left, so when he again went to Andersonville he would have a supply to start with. That night, the poor fellow died, raving about something to eat. Two days later, his wife came down, expecting to take him home. He belonged to an Indiana regiment.

We were still in charge of the Rebel Major, and the way the bottom was being knocked out of the Confederacy, he found it very slow work to get a like number of rebs from Rock Island to exchange for us so he could make the trade and return South. About two o’clock one night, we received the news that Lincoln had been murdered. One who was not there cannot realize the feelings of those prisoners when they heard the account. I think we felt worse than the soldiers in the field! A few of us cut a rope from a tent and went for our rebel major with a firm intent to hang him to a pine tree that stood near, in retaliation, but in some way he got wind of our movements, and was gone, and next morning, he was nowhere to be found. We kept quiet and said nothing about our “neck-tie party”. I do not remember the names of any of the “party” or the regiments to which they belonged; but if this should ever be seen by any of those “boys”, I want to hear from them.

The next morning, they began work to ship North all who were able to go. The Sultana, a large boat, was loaded with over 2,000 persons. I begged to be allowed to go; but the doctor in charge said I was not able and must wait for the next boat, which I did, going up the river on the Baltic, to Jefferson Barracks, Mo. The Sultana, on the second night out, was blown up and some 1,600 lives lost, after they had braved death in the different rebel hells! They were so near home and liberty and were to be either blown to pieces or find a watery grave, by the traitor’s devilish work of placing a torpedo in the boat’s coal. The fiend who did it, acknowledged it in St. Louis, in 1887.

I was now down again unable to walk, with a large abscess back of the knee of my left leg, and I had to be carried to the boat on a stretcher. Before I was put in my berth, I saw a passenger run and jump overboard. They had had hard work to get him on the boat, as he thought they were taking him to another rebel prison! He had been lied to so much, and his mind being affected, he could not believe his own brother, who had come from Chicago to take him home. I did not learn whether they recovered his body. He belonged to the 85th or 86th Illinois.

When we reached Jefferson Barracks, I was out of my head. I do not remember anything about landing. When I became rational, I found myself on a clean cot, and my blue suit replaced by a clean shirt and a pair drawers. A man and woman were standing looking at me. She asked him if he thought I would live. He said the chances were against me. I closed my eyes and heard them talk of my chances and what I had been talking about while out of my head. They said I would talk about a wife and four children one minute, and d–n the rebels and old Wirz the next. This surgeon and his good wife were from Wisconsin. I would like to learn their names and address. I wrote the Assistant Adjutant General of the State, several years ago, but he failed to find any record of them, as they were probably detailed from some headquarters.

I heard him tell his wife to watch me closely and if I awoke in my right mind, to send for him at once, as he wanted to open the abscess and also to tell me that my wife would soon be there. When I awoke, she gave me something to drink that had considerable whiskey in it. She told me where I was and how I got there. The first thing I asked for was something to eat. I told her that it did not seem that our government was determined to finish the starving the rebs has so well begun; she smiled and said I could have anything I wanted, so I ordered six eggs; but do not remember what else; all of which she said I could have; but instead of getting them, the doctor came and took a look at my leg and told me it had to be opened at once or I would not live twenty four hours. He said the surgeon at Vicksburg ought to be discharged for not attending to it before I was put on the boat. I wanted him to give me some anesthetic while he ran his lance in, but he said–“No, you are too weak to stand it. To be plain with you, now that you are in your right mind, the chances are ten to one against you.” My leg was more than double its usual size. While he had been talking to me, he had thrown off the cover. The ward nurse had come in to assist in the operation.

His wife put her arms around my neck, put her face down to mine and gave me a good hug; when he, at the same time, ran his lance into my leg. His man was on hand with a basin. I fainted, although there was no pain. When I came to, I found they had taken out a pail of matter.

I began to improve from that time. I had written to my wife from Vicksburg, that we were to be sent to Jefferson Barracks, and I would be home as soon as I was able to travel. A few days, (I do not remember how many,) after were the operation, as I lay on my cot, (I had not yet tried to walk or stand,) who should walk in with the doctor, but my wife and brother John! To say that I was surprised, would be putting it too mildly. It was rather too sudden for me just at that time, and they say I did not want to go home; but next morning they started with me. With a pair of hospital crutches and their help, I could get along.

The Post Surgeon would not let me go unless I took my discharge (June 19, 1865,) which I ought not to have done, as I did not do any work for years; and after twelve years, I received a pension of four dollars per month! and am still (June, 1888) drawing that amount, with a constitution wrecked by exposure and starvation in the five living hells I was confined in–Andersonville, Savannah, Millen, Blackshear and Thomasville, and the old arch traitor (who caused, or at least appointed and retained in office Wirz and Winder and sanctioned and approved their devilish methods of slaughter,) is still alive and enjoying all the blessings of this free country he tried so hard to destroy. Hell will never be complete until he is there. If Jeff. Davis is not consigned to the warmest corner of it, the other world should be entirely obliterated.

“Solider, rest, thy warfare o’er!”

Hie thee to thy home once more,

There may our saved, united land

Reward thee, with a grateful hand.

THE END

Editor’s Prologue (K. Hawthorne): Captain Henry Wirz, of Andersonville Prison was arrested and “accused of committing 13 acts of personal cruelty and murders in August 1864: by revolver, by physically stomping and kicking the victim, by confining prisoners in stocks, by beating a prisoner with a revolver and by chaining prisoners together. Wirz was also charged with ordering guards to fire on prisoners with muskets and to have dogs attack a prisoner.” (Wikipedia). He was found guilty on several counts and hanged on November 10, 1865.

Magnus Tait survived his ordeal but was never the same physically and his experience as a prisoner of war and the cruelties he suffered and witnessed haunted his memories. He died September 19, 1906 in Santa Clara County, California.

Magnus Cooley Tait, son of Magnus and Antoinette Tait, owned a home, built in about 1886/87 at 511 North Tremont Street. It still stands today.