Marion Brashears Gill has long been relegated to a footnote in the history of her famous husband, acclaimed California architect Irving J. Gill. Little has been written about her and even then it is often repeated misinformation. I sought to find all I could about this woman who captivated Irving’s heart, his one and only marriage in the later years of his life. Although I have spent over a year and gathered nearly a thousand pages of documents about her life, her marriages, her varied occupations, Marion, once described as an enigma, remains mysterious.

Marion Agnes Waugh was born May 31, 1870 in Apple River, Illinois. She was the only child of Charles J. and Jean (Sutherland) Waugh. The Waugh family moved to Peabody, Kansas, located in Marion County, about 45 miles northeast of Wichita. The town of Peabody had a population of just over 1,000 people in 1880.

In her younger days, she went by the name of “Mary” and attended the Peabody grammar school. In 1882 she was listed in the roll of students with her teacher noted as Mr. R. M. Williams.

Her father Charles owned and managed the Little Giant Custom Mill in 1885 which was located “at the foot of Walnut Street” near the bridge. Waugh owned a substantial farm four miles south of Peabody which he owned for decades even after he left town. He was also a building contractor, erecting several early homes in Peabody including the homes of “Senator Potter” and C. E. Westbrook.

When Marion was just 13 years old, Marion’s parents divorced in 1883, with her mother citing “extreme cruelty” by her husband. Mrs. Waugh and daughter Marion left to live in Chicago.

In 1889 mother and daughter were living at 377 Winchester Avenue and Marion was working as a clerk in the Pullman Building in downtown Chicago. In the directory of that year, Jean Waugh’s marital status was listed as “widow of C. J. Waugh.” This was a common practice used by many women, because of the stigma of divorce.

Marion made annual visits to Peabody, Kansas to visit friends as noted in the Peabody Gazette, particularly visits in October 1889, October 1890 and July 1891. She traveled the 675 miles by train. Her father moved to Mullinville, a small town in southeastern Kansas, but he still retained property in Peabody.

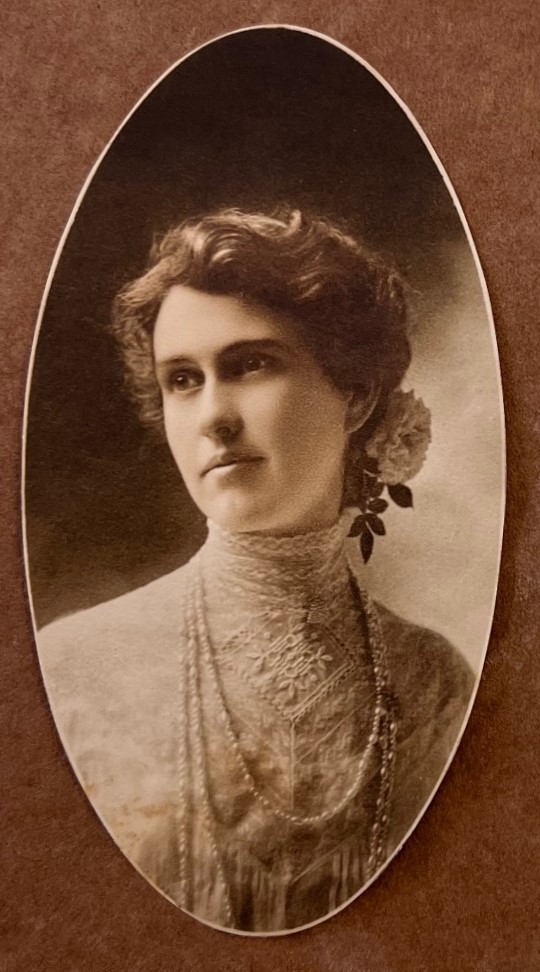

In 1892 Marion was listed in the Chicago directory working as a bookkeeper and living in an apartment at 180 Wabash Avenue. The Gibson Art Galleries, a photography studio where Marion had her photo taken, was on the same block at 190 Wabash Avenue. It is more than likely she visited the studio because of its proximity. Marion may have been around 22 years old at the time the photo was taken. In it she is wearing a striped blouse, silk scarf and a large hat. She gives the camera only a hint of smile.

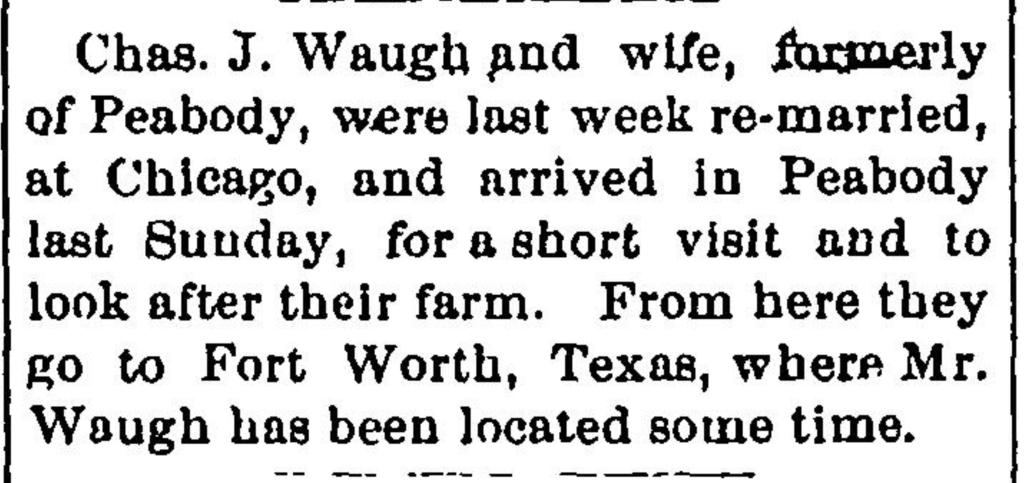

On September 26, 1893 Charles and Jean Waugh reconciled and were remarried in Chicago. The couple then moved to Fort Worth, Texas, where Charles Waugh had relocated earlier.

Marion remained in Chicago and that year filed a lawsuit against banker Frank R. Meadowcroft for $500. Meadowcroft’s bank failed and he and his brother were arrested for embezzlement six months later, charged with mishandling and spending thousands of dollars belonging to their customers. The pair were eventually sentenced to one year in prison but Marion, along with others, was out her monies.

Marriage to Brashears

In spite of the financial loss, Marion celebrated her nuptials on August 15, 1894 when she married James Bradley Brashears in Chicago. Brashears was a clerk and traveling auditor for the Chicago North Western railway company and the nephew of John Charles Shaffer, a major newspaper publisher who made his fortune in railroad investments. Years later Shaffer would be misidentified as Marion’s uncle, but it is likely she that provided that information.

The newlyweds made their home at 525 Marion Street in Oak Park, Illinois in a large Victorian home. The following year the couple relocated to Evanston, Illinois to a home at 1305 Judson Street. While in Evanston, Marion opened a “hair salon” at the corner of Davis Street and Chicago Avenue in 1895. An advertisement she ran in the local paper indicated she was formerly with E. Burnham, a popular salon owner with two locations in Chicago.

James and Marion Brashears resided at their home on Judson Street through or up until 1904 when the couple may have separated for a time. James was traveling to Michigan for the railroad company, as noted by various newspaper reports. Marion went to Portland, Oregon and rented a room at Mrs. Gertrude Denny’s boarding house, 375 16th Street, long enough to be included in the residential directory of that city.

The following year Marion’s parents moved from Texas to Highland Park, California, a suburb of Los Angeles. There Charles purchased several lots in the city, built homes and sold them.

Marion apparently returned to Chicago from Portland in or around 1906 where she and James resided at 2000 Kenmore Avenue. Marion would later claim to have lived continuously in the Chicago area until 1908 but neither she nor James could be located in any directory published around that time.

Ethelbert Favary

By the summer of 1908 Marion had again left Chicago, traveling once more to Portland, Oregon. By 1909 she was selling shares for the Favary Tire and Cushion Company, and was presumably there to conduct business. Just how and when Marion entered into this business venture and met the company’s owner Ethelbert Favary is unknown, but it certainly changed the trajectory of her life.

Ethelbert Favary was a native of Hungary, born in 1879, immigrating to the US in 1902. One of the first records of him is from the Wall Street Journal on March 2, 1909 announcing the incorporation of the Favary Tire & Cushion Co. in New York with “a capital of $1,000,000” and listing the directors: Ethelburg [sic] Favary, Joseph Nordenschild, and C. S. Block.

In spite of his New York connection, Ethelbert Favary was a resident of Portland, Oregon as he was listed in the 1909 Portland directory as an electrician and renting a room at 741 Washington Street. On March 7, 1909, the Oregon Daily Journal published an article entitled “An Automobile Tire Without Rubber” in which it briefly introduces Favary: “A new automobile tire, which its promoters claim will revolutionize the entire automobile industry, has been invented by E. Favary, a young Portland inventor. The tire contains no rubber, no air and no springs and is more resilient than the present pneumatic tire.”

Back in Portland, Marion returned to the Denny Boarding house she had resided years earlier. It was during this second Portland residency that Marion became involved in a scandal or series thereof that would later result in a lawsuit.

Denny Boarding House

While at the boarding house Marion met and became acquainted with Reverend Nehemiah Addison Baker, a young preacher of the First Unitarian Church in Portland. The Reverend and Marion both rented rooms on the third floor, but another room separated them. The two were friendly enough that Marion visited Baker’s room on several occasions, many of them considered “after hours” visits. Baker would later insist that the visits were innocent and that the two simply talked and sometimes read passages from “Dante’s Inferno.”

Their friendship did not go unnoticed by other tenants, especially the late-night visits. It was reported to the landlord that Rev. Baker asked Marion to leave his room in a loud and abrupt manner. Baker would later deny that he had ever asked Marion to leave his room and that nothing inappropriate happened between them.

While at the Denny boarding house, Marion was visited by Ethelbert Favary. Marion was selling shares of the Favary Tire Company and was said to have been his personal secretary. Favary conducted business or met with Marion there somewhat regularly. Curiously, he kept a typewriter in the room of Rev. Baker.

The relationship between Marion and Ethelbert raised eyebrows as the two locked themselves in the parlor of the boarding house on more than one occasion. Marion would insist they needed privacy to attend to business matters. Tongues wagged when they were seen on a street car together on Christmas morning. Perhaps this behavior would hardly be noticed today, if at all, but this was just a few years after the Victorian era, where there were certain protocols of acceptable behavior between the two sexes.

In addition to what was viewed as unsuitable behavior, Marion was accused of being forward and overly flirtatious with other men involved in the Favary Tire Company. On one occasion Marion came in briskly to an office and asked the wife to leave as she needed privacy…with the woman’s husband.

Marion would claim that the gossip about her alleged behavior caused her great distress, causing her to lose sleep and have what we would term a nervous breakdown. A doctor was called, as was her husband, James Brashears, who traveled to see her when notified of her condition.

However, this distress could have been brought on by the departure of Ethelbert Favary, who left Portland to marry Victoria Morton. Favary relocated, at least briefly to Boston, giving his address as 10 Cumberland Street on a marriage application. The couple married in New York on April 9, 1909 by a rabbi at 265 West 90th Street.

The marriage was brief. Victoria claimed that her husband abandoned her shortly after the marriage. While separated Ethelbert apparently paid a sum of support to Victoria, which amount was soon reduced and then ceased altogether. He traveled to London in 1911 and upon his return Victoria had him jailed in the Ludlow Street Jail for not paying her financial support. Ethelbert refused to pay and spent at least four weeks in jail.

Favary would marry another four times but he somehow remained a connection with Marion for decades and one that would take them across the country and back again.

Rumors among the boarding house residents, Marion’s business associates and others, suggested that Marion was distraught and physically ill after an abortion. Because of their intimate walks and talks, Reverend Addison Baker was thought to have been the father.

Whatever the reason of Marion’s distress, Mrs. Gertrude Denny did not want the gossip, the scandal or the hysterics in her dignified boarding house. She raised Marion’s rent so high that in response Marion left, although she remained in Portland for a brief amount of time.

It is unknown where Marion traveled next. She may have gone back to Chicago, although no record for her could be found. However, in 1912 Marion is found living in New York City and she is also listed as one of the incorporators of the Favary Tire Company!

It was reported that a plant located in Middletown, New York would soon begin producing tires. It is unknown if the plant ever produced a single tire and the company was sold or liquidated by 1915.

Slander Lawsuit

Months later, in April 1913, Marion filed a $50,000 slander lawsuit in New York District Court against Susan W. Smith, a former “partner” in the Favary Tire Company. Smith was a native of Alabama, born in 1855, and the widow of Preston C. Smith. The women met while in Portland selling shares of stock. There may have been some competitiveness between the women as Marion let it be known that she had sold 1,000 shares of Favary stock but Smith, with her “reputed business acumen” had sold only 137 1/2 shares.

While Marion’s original complaint was not available for review, Susan Smith’s answer was and in it detailed the conversation that culminated in litigation:

“In the spring of 1909, at the corner of Clay and 13th St., in Portland, Oregon, Marion Brashears told Susan Smith that a certain George K. Rogers, a promoter of the Favary Tire and Cushion Company, by which said company Marion Brashears was then employed, had insulted her by saying “Don’t you come so near me. My wife does not like it and neither do I.” Whereupon Susan Smith said to Marion “Well, I would never enter his office again.” Whereupon Marion replied, “What? Give up my business career because that man insulted me? Never.” Susan Smith then learned from further conversation with Marion Brashears that she did not resent or feel shamed at being so addressed, and did not seek to avoid further similar insults.”

However, Marion did in fact resent that conversation but she waited four years before filing suit against the woman she deemed solely responsible for spreading rumors about her. The lawsuit and subsequent trial made headlines from coast to coast, including Portland, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and everywhere in between.

Before the case was publicized, however, on June 9, 1913 Marion’s mother Jean Waugh died at the age of 71 in Los Angeles. Two published obituaries of Mrs. Waugh do not mention her daughter.

A myriad of depositions were taken before Marion’s case went to trial. Marion was described as a “wealthy widow” in newspaper accounts. Marion described her once former friend and partner, Susan W. Smith, as the “Hetty Green of Portland, Oregon,” a very wealthy New York businesswoman said to have lived miserly.

When Smith testified, she said that her comments were private ones concerning Marion and that she had simply warned a younger woman “not to be too chummy” with Mrs. Brashears, “lest her reputation be impaired.”

The gossip also seemed to be second hand. “I told her,’ sobbed Mrs. Smith, “that Mrs. Denny told me that Mrs. Taylor told her she had overheard the Rev. Mr. Baker exclaim to Mrs. Brashears, ‘For God’s sake, leave my room!'”

If Marion wanted to save face and protect her dignity, the suit had the opposite effect. Details of the accusations and testimony of dozens of witnesses were published on the front pages of numerous newspapers across the country. Salacious selections of testimony and contents of depositions were printed about Marion and what was seen as her forward behavior toward men, including Rev. Baker, Ethelbert Favary, and a married man under the disapproving eye of his wife.

Testimony of George K. Rogers

George K. Rogers, a witness for the defendant, was asked what occupation Marion may have held before she began selling shares in the wheel company. He answered: “Well, I don’t just exactly know. I understood when I first became acquainted with her that her occupation was an interior house decorator, or something of that kind, artwork, or something. She became interested in the device I was handling and aided considerably with my work in connection with the inventor. I might almost say she changed her occupation for that work.”

He spoke about Marion’s unwanted behavior that he considered inappropriate and that he felt strongly that Marion wanted to have sex with him. “On some occasions in the office, she would want to emphasize some remark she wanted to make, and she would come up and tap me on the breast. I told her at one time we could do business without such familiarity and I thought it better she keep a little distance.“

Rogers also mentioned that Marion would stand very close, or even against him when signing company documents. His wife would testify that in her presence Marion would “corner” her husband, “standing against” to speak with him.

Susan W. Smith

While it seems that several people had very strong opinions about Marion Brashears, she only sought out to sue Susan W. Smith. The slanderous statements Marion claimed that Susan Smith repeated about her were as follows (per the deposition transcripts):

- Mrs. Brashears had been forced to leave the boarding house in Portland and that she was not a fit associate for anyone; and was an immoral character.

- Marion further alleged in her complaint that her former business associate Susan W. Smith said, “I will make it so hot for her, that she will be obliged to leave Portland. I will make it my business to ruin her reputation with anyone she knows.”

- She (Marion) goes into the room of Dr. N. A. Baker, a clergyman, at night, and you know there is only one reason for a woman to go into a man’s room at night, an immoral one. I know she is criminally intimate with this young man. I want you to know I am a southerner and I can hate. She (Marion) was a bad woman. She was Mr. Favary’s mistress. She had tried to tempt Mr. Rogers.

The most scandalous remark Marion alleged Smith said was that Marion “had been guilty of intimacy with this minister, Rev. N. A. Baker and had had an abortion which was the cause of her sickness.”

Testimony of Reverend Baker

In his testimony Rev. Nehemiah Addison Baker recalled meeting Marion Brashears in July of 1908 and that while residing at the boarding house, Marion would come to his room at night and stay as late as 11 o’clock, sometimes till midnight. When questioned about their activities, Baker said they would read together.

Baker said that Marion would come in his room when he returned from meetings or appointments. “I got home at 9 perhaps 9:30 and she might get home at 9:30 or 10 and she would come in; and there has been some reference to midnight, and I doubt if that was more than once or twice.” He was asked if he had ever asked Marion to leave his room and he said no.

When asked how old Mrs. Brashears was, the much younger Baker answered, “Did she seem to be to me? It was an enigma. I never attempted to surmise. It was immaterial to the situation.“

When asked about Ethelbert Favary, the minister said that he knew Favary had visited Brashears while she was at the boarding house. He said, “I know he came to the house and visited her in the parlor of the house. I believe I did hear some comment, I cannot tell you where it came from now, that the door was locked.”

When asked if Mrs. Brashears ever made any advances toward him, Baker said no. But when he was then more pointedly asked, “Did she make any advances when you and she were together?” He answered, “Well, my understanding of advances might be different from what would generally be accepted.” He then went on to describe an occasion where they went for a walk. “I think she took my arm, in such way to escort herself, or help herself on the path.”

He was questioned: “Did her action at that time impress you as being a little improper?” Baker answered “I don’t know, as there was any impropriety in it, in taking a gentleman’s arm, but it surprised me, that is all.”

His response brought the next question: “Why did it surprise you?” To which he replied, “Because I thought it might’ve been more my place to have taken the lady’s arm, if there were any need of such an escort.”

Further questioning continued: “Did she at any time embrace or attempt to embrace you?” He answered. “Well, only this occasion I speak of, I might have interpreted that.” Baker went on to say that Brashears “bore herself as a perfect lady in every way, or otherwise I would not have been comfortable under such association.”

When asked, “Was there anything intimate or caressing in the manner in which she took your arm?” Mr. Baker replied, “I thought so at the time.”

“In what way did you think it was particularly caressing?” Baker answered, “Well, I suppose by intensity.”

“Because she held your arm tight; was that the reason?”

“Yes sir.”

“When it came to relinquishing that hold, you were the active factor?”

“I believe I was.”

“You withdrew your arm?”

“Yes sir.“

Under cross examination Baker was asked if he and Marion “ever spoke of personal love” between them and he answered, “Never.”

“Did you ever discuss that topic generally?”

Baker replied, “I discussed what I would call the larger social relations.”

“And that included matters of affection, matters of sex, and matters of family life?”

Baker responded, “Yes sir.”

“Did Mrs. Brashears ever speak to you of her husband?”

“Yes sir.”

“Did you ever caution her that her husband might possibly misinterpret her conduct?”

“No sir.”

Baker also added that he had no other association with other women in the house.

What did Marion hope to achieve by her lawsuit? Did she know or realize that the trial would be so sensational? Was she humiliated or delighted?

Marion, who was described in newspaper reports as “pretty” and “willowy” defended her late night visits to the minister’s room, saying, “Rev. Mr. Baker is a most devout and sincere man. Many of the other boarders went to his room just to be cozy when their own apartments were not warm enough.”

The trial came to an end on November 12, 1914 with Marion Brashears losing her lawsuit and having to pay attorney fees for the defense of Susan W. Smith.

Divorced

Marion was back in court in May of 1916 when she filed for divorce from her husband James Bradley Brashears, claiming he had abandoned her. Marion hired attorney Alice Thompson, a progressive choice for the time. Thompson was co-owner of a woman-owned law firm, Bates & Thompson, in Chicago, Illinois.

James Brashears claimed in his answer that he had never left Marion. He traveled in his work for the railroad, and newspapers reported some of his trips on behalf of the railroad.

In the divorce papers Marion claimed that she had been a faithful and loving wife and had maintained her home in Chicago until 1908 (although she was living in Portland, Oregon in 1905) and that she herself traveled for business purposes. She was granted the divorce.

In August of 1916 Marion was staying in Beachwood, New Jersey, a “summer colony” near the metropolitan area of New York City where she was elected publicity chairman for the Beachwood Property Owners Association. The following month she was elected President of the Beachwood Women’s Club.

Marion purchased a summer home at 424 Beacon Avenue in Beachwood in about 1919 but in early 1920 she was in California where she purchased property in Highland Park, where her father resided and sold her Beachwood cottage a year later.

New Era Expression Society

In July and August of 1920 Marion conducted lectures in San Francisco on “worry” and “personality” for the New Era Expressions Society. The New Era Expression Society provided a forum for followers or members to “express ideas on personality, inspiration, psychology, Raja yoga, ethics, philosophy, elocution, poetry, public speaking, music, drama, self-culture, short talks, and exchange of ideas.”

Marion was touted as a psychologist in one of the ads and it is likely her association with the New Era Expression Society that she took on her role as a “vocational analyst.” This appears to be a “gift” rather than a science, determining a job or career for clients. At times these analysts also ran ads for palm and character readings.

In 1921 Marion was living at 5101 Almaden Drive in Highland Park, California, along with a local teacher and private tutor, Edith E. Beamer, who was likely renting a room from her. Two years later Marion was residing at 4620 Fifth Avenue in Los Angeles, again with Edith Beamer.

Death of Charles Waugh

Marion’s father, Charles Waugh, died October 15, 1923 at the age of 84. Charles had been living with Alva and Daisy Bahen at 5127 Range View Avenue in Highland Park, California. The couple had been caring for Marion’s ailing father and Daisy had been his housekeeper for several years up until he moved in with the Bahen family.

Likely the sole heir to her father’s estate, the following year Marion was sued by Daisy Bahen for $10,000. Daisy claimed that Charles Waugh had promised her this sum for her services and long term care. It is unknown how this lawsuit was resolved. [The court case was unavailable from the Los Angeles County Superior Court Archives, along with the probate case of Charles J. Waugh.] Marion was also sued by attorney L. T. Mayhew, who handled her father’s estate, for the sum of $458.52 for nonpayment of services.

One month after her father’s death, Ethelbert Favary, Marion’s alleged lover and business associate, moved from the east coast to Southern California. Is this merely coincidence? Did Ethelbert come to Los Angeles to woo Marion? Did she refuse him or did he refuse her?

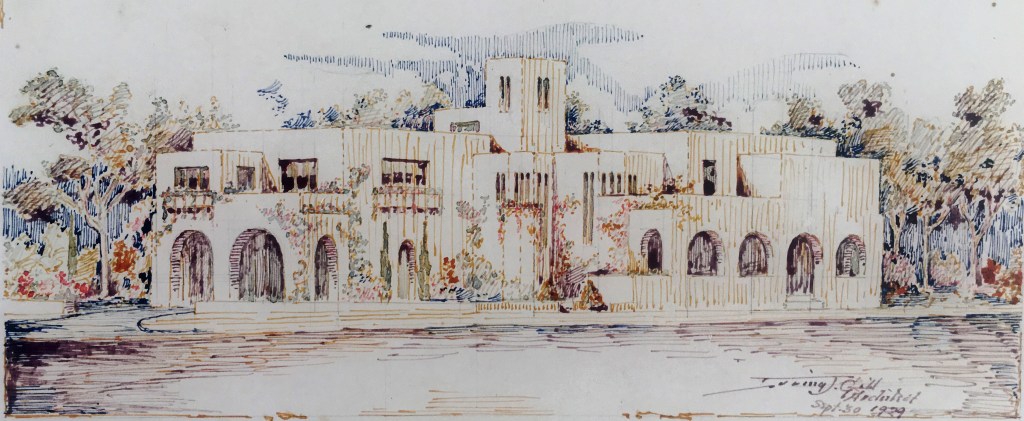

In 1924 Marion moved into a home at 2325 Via Panale in Palos Verdes Estates, designed by architects David Witmer and Loyall Watson. The beautiful home was built in the Mediterranean Revival style. Marion hired renowned architect Irving J. Gill to design the home’s landscape.

While it is unknown how much money or property Marion inherited from her father’s estate at this time (while waiting on records to become available) she was said to have invested money in the Julian Petroleum Company. It collapsed in 1927 after it was discovered the owner, Courtney Chauncey Pete, defrauded local investors of $100 to $200 million. It was the second time Marion had lost money by fraud, and this may have been a substantial sum.

Favary Marriages

If Favary was only interested in Marion’s money now she suddenly had none or a lot less. (Of course, this is only speculation.) While Favary’s company was once valued at $1 million, it is unknown if the tires were ever mass produced.

On January 8, 1928 Ethelbert married his second wife, Mary, in Tijuana, México. While the marriage lasted nearly six years, in 1934 he petitioned the court for an annulment of the marriage. The reasons listed for his request for an annulment was that “the parties were not acquainted with the witnesses to the purported marriage for a period of two years or at any time at all” and that neither Ethelbert nor Mary had “submitted to a physical examination by a physician or anybody purporting to be a physician.”

Apparently, this flimsy argument after a six-year marriage was sufficient and Favary was granted the annulment in 1934.

Favary then married Edith L. Bowslaugh on March 30, 1935 but this time it was Edith who filed for divorce or annulment that same year. Edith said the couple separated after just four months after Ethelbert treated her “in an extremely cruel and inhuman manner“, and “inflicted cruel and mental suffering” upon her.

Edith alleged that her husband had misled her about both his occupation and income. Before their marriage, Ethelbert told Edith that “he had sought the world over for a mate and felt that he had found her.” After the marriage Edith had deposited “all of her income in a joint bank account” and gave Favary access to the same, which he spent for his “own personal gain.”

On top of that, the couple lived in a small three-room apartment at 453 1/2 Tujunga, in Burbank, California, occupied by 3 dogs, 20 lovebirds, 20 canaries and one parrot. Ethelbert told Edith it was “her duty as his wife to look after the care, maintenance and comfort of the animals; that were his real love motive in life that they were his children and that she should be satisfied looking after the animals and birds” and willing to help pay for their “maintenance.”

If that wasn’t enough humiliation, and most telling, Ethelbert told Edith, before they were married that “he could have married a woman who had $1 million” and by “innuendo made her feel that he had made a mistake by doing so.”

Who, other than Marion, could Ethelbert be referring to?

Edith was granted her request for annulment on October 9, 1935 by Judge Clarence L Kincaid. Ethelbert then married Bertha Hirson in Ventura in 1936, who died in 1945. His fifth marriage was to Sadie Lang Gross in 1950.

Marriage to Gill

On May 28, 1928, Marion and Irving J. Gill were married at her home in Palos Verdes. The marriage announcement was published in Time Magazine, which stated that Marion was a “vocational analyst” and “the niece of potent Publisher John C. Shaffer (Chicago Post).”

This occupation and her supposed relationship to Shaffer would be repeated in other newspapers, and then later, biographies written about Gill and his marriage to Marion. Again, it was her ex-husband who was the nephew of Shaffer. It stands to reason Marion herself would have provided this information for reasons unknown. Also misleading, on the marriage license to Gill, Marion indicates that she is a widow, rather than her actual marriage status as divorced.

The San Diego Union reported that the marriage was the “culmination of a 10-year romance.” Several writers/historians have suggested the couple may have met while living in Chicago decades earlier. It is more likely that Marion and Irving met some time after she moved to California between 1920 and 1924, or when he designed the landscape for her Palos Verdes home.

Carlsbad

Two weeks before their marriage, Marion purchased property in Carlsbad. The Oceanside Blade Tribune reported that: “Mr. and Mrs. Edward Glasscock have sold their acre home site in the Carlsbad Palisades for $13,500. The purchaser is a Los Angeles woman, and announces her intention of building one of the most beautiful homes in Carlsbad.” The property was located on the southeast corner of Pine and Lincoln Streets.

While writers have speculated that it was Marion’s family who owned property in Carlsbad that she in turn inherited, nothing could be found to substantiate this after a search through recorded deeds in the San Diego County Recorder’s Office. What was discovered is that Marion herself purchased properties in Carlsbad and they were recorded as her sole property.

Irving Gill was in Carlsbad two weeks before the nuptials, along with John S. Siebert, another San Diego architect. The two men were making a survey of the Newberry Mineral Spring property to design a new “Health Hotel.”

The Carlsbad Journal reported: “Mr. Gill, who is the originator in San Diego of a plain, practical and dignified style of architecture, is enthusiastic over the opportunity on the Spring property for producing a group of buildings with landscaped surroundings that will command the admiration of all lovers of architectural beauty.

“It is expected that he will be retained for other work in prospect for Carlsbad, and it is his purpose to create a particular design which he will christen ‘Carlsbad architecture,’ one that will set this city out as one of the most attractive communities on the Broadway of the Pacific.”

The following week it was announced that Gill had plans to move to Carlsbad: “Irving J. Gill, San Diego architect, who is drawing tentative designs for the new Carlsbad Mineral Spring health hotel, was in the city yesterday, and attended the noon luncheon of the Chamber of Commerce. In a brief talk to the club Mr. Gill intimated that his future plans contemplated a home in Carlsbad, and in that connection proceeded to say that he considered Carlsbad as offering the greatest opportunity for the development of a new architectural fashion of any place on the coast.”

Again, Gill remarked that he had conceived an “entirely new type of architecture designed with its future program in view and one that will command the attention and respect of culture and wealth” to be known as “Carlsbad architecture.”

Marion and Irving were living in San Diego just after their marriage. Marion gave a San Diego address on the deed for the Glasscock property, when it was recorded June 2, 1928.

In July of 1928 the Carlsbad Journal reported: “Mr. and Mrs. Irving Gill of San Diego were in Carlsbad Monday looking after their property interest and calling on friends.”

Unfortunately for Irving Gill, he was not selected to design what would become the Carlsbad Hotel on Carlsbad Boulevard and Gill’s “Carlsbad architecture” never came to fruition.

The Gills then lived in Palos Verdes for a time but visited Carlsbad frequently. Their visits were included in the local paper. The September 28, 1928 issue of the Carlsbad Journal reported: “Mrs. Irving J. Gill of Palos Verdes spent today at her Carlsbad avocado ranch, and had as her guests, Mrs. Joseph Bushnell of Chicago, Chicago, Mrs. Edgar Brashears of Walnut Park, and Mrs. Charles Blodgett of Huntington Park.“

Mrs. Edgar Brashears was Marion’s former sister-in-law. Edgar was the brother of her ex-husband James Bradley Brashears! Edgar K. and Virginia Brashears moved to Southern California in about 1925. (Certainly they knew Marion was not a widow!)

In November of that year, another visit was noted in the Journal: “Mr. and Mrs. Irving Gill of Palos Verdes, accompanied by their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Snyder, visited their avocado ranch at Carlsbad Saturday.” The avocado ranch was on the one acre “home site” Marion purchased in May. The 1929 Sanborn maps show a small house near the corner of that property.

The article went on to say that “Mrs. Gill is much interested in the civic welfare of Carlsbad and has presented a silver loving cup to be awarded to the individual or organization performing the most practical and outstanding civic act in 1928. The cup is on display in the Journal office.” (If the silver trophy was actually awarded to anyone, no mention of it could be found.)

Other visits memorialized in the Carlsbad Journal were as follows:

January 11, 1929: “Mrs. J. Irving Gill of Palos Verdes was here over the weekend looking after her property interests and was a guest in the home of Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Armstrong.”

January 25, 1929: “Mr. and Mrs. J. Irving Gill of Palos Verdes Estates were weekend guests of J. W. Armstrong and family going from here to San Diego. Mrs. Gill was looking after her avocado grove on the Palisades.”

March 1, 1929: “Mr. and Mrs. J. Irving Gill of Palos Verdes Estates, who have been spending a week on their Carlsbad Ranch, had as their guests over the weekend, Mrs. John W. Mitchell, proprietor of the Mitchell art galleries at Coronado.”

March 22, 1929: “J. Irving Gill of Palos Verdes Estates spent several days this week in Carlsbad personally supervising his avocado ranches here.”

March 29, 1929: “Miss Edith Beamer of Palos Verdes Estates accompanied her friend Mrs. Irving Gill to Carlsbad the first of the week for a short visit. Mr. and Mrs. Gill are spending some time here superintending their avocado lands.”

Living Separately

By the summer of 1929 Irving Gill was spending “the summer” in Carlsbad. Had Marion and Irving legally separated? It is likely Gill wanted to remain in Carlsbad to work on a variety of projects, including the fire and police station in Oceanside, built that year. He would later design the Americanization School, Oceanside City Hall building, the Nevada Street School, a private home at 1619 Laurel Street in what was then referred to as North Carlsbad (now Oceanside) and his last work, the Blade Tribune newspaper building.

In June of 1929 the Carlsbad Journal reported that he was “preparing the plans for the new W. F. Oakes residence in Paradise Valley.” Paradise Valley was a neighborhood near or around Valley Street in Carlsbad.

The home’s description was as follows: “The house will have 10 rooms, including six bedrooms, with four baths, sunrooms, living rooms, done in the Gillesque style of architecture, buff, stucco, plastered roof, and build adapted for extensive landscaping. It will be one of the most beautiful homes in Carlsbad and will introduce the new architecture into this district.” (Whether or not Gill designed the Oakes home, the family lived at 1281 Magnolia Avenue. A house located there, in a Spanish eclectic style, has been extensively remodeled.)

After one year of marriage, it was reported that Irving “went to Palos Verdes Estates last week to be with Mrs. Gill on their first wedding anniversary.” In July Marion visited Irving twice, however she stayed at Carlsbad’s Los Diego Hotel rather than the modest house located on her property.

In August of 1929 the Carlsbad Journal announced that “Irving J. Gill, who has been resuscitating on his Carlsbad avocado ranch the past two months, has opened an office in the Scheunemann building on First Street (State Street) to resume intensive work on architectural maps and drawings. Mr. Gill, who enjoys national fame as one of the leading American architects, has a number of commissions to execute, and has equipped his commodious office space with the necessary paraphernalia for the work.”

Later that month announcement was made that Gill would help form and instruct an architects’ club for local students, but it is unknown whether this club was actually formed.

In early September a visit from Marion was noted, but on September 27, 1929 the Carlsbad Journal reported that Gill had been seriously ill. “Architect Irving J. Gill has almost completely recovered from a sudden and severe attack of illness last week.”

Gill’s “summer” residency in Carlsbad continued to the fall and winter. In December of 1929 he was one of several men who were vying for a spot on the Carlsbad Chamber of Commerce. Gill was not selected, however, which seems a missed opportunity for the town of Carlsbad.

Irving spent the holidays with Marion in Palos Verdes. Her visits to Carlsbad seemed to wane. Although E. P. Zimmerman, a Gladiola grower in Carlsbad, named a gladiola for Marion in early 1930, another visit was not reported until the May of that year. The 1930 census records indicate that Marion was still living with or renting a room to Edith Beamer.

Irving visited Marion in June of 1930, the couple attended the dedication of the new Palos Verdes Library.

In September of 1931 Marion bought Lot 7 and 8 in the Optimo Tract, and then Lot 11 of the same Tract. The lots were located on Eureka Street, with Lot 7 being on the corner of Eureka and Chestnut Streets, which borders the southeast corner of Carlsbad’s Holiday Park east of Interstate 5.

One year later Marion sold or transferred these lots to her friend Edith Beamer. Edith would later sell or transfer them back to Marion and they exchanged ownership again at least twice.

Wine Lawsuit

While researching Marion in a variety of newspapers and publications, it was discovered that a lawsuit had been filed by a “Mrs. M. W. Brashears” in or around October 1931 in Visalia, California. This lawsuit involved a “woman from Los Angeles” who was a school teacher. In the 1930 census Marion Gill’s occupation is listed as a private teacher.

Editor’s Note: It is my belief that Mrs. M. W. Brashears is Marion Waugh Brashears Gill, who was living in the Los Angeles area and was purportedly a teacher, private or otherwise. There were no other women (or men) found in Los Angeles County with those same initials and last name. In a tax delinquency report in 1929 in Palos Verdes, her name is given as M. W. Brashears Gill.

Why would Marion use her former married name instead of her current one? It could because she had attempted to purchase 30,000 gallons of wine during the Prohibition era for resale and distribution.

Two years earlier, on December 14, 1929 Marion entered into a contract with Frank Giannini, a Tulare County rancher. In the lawsuit that precipitated, Mrs. Brashears aka Marion Gill, told the court that Giannini agreed “to sell her the wine at about $.55 a gallon, assuring her that she could dispose of it to rabbis, priests and ministers who needed it for sacramental purposes at the rate of $1.50 a gallon.”

She also alleged that Giannini told her that she could sell the wine without violating the law when signing the contract involving 30,000 gallons, making a down payment of $6000. Newspapers reported that the wine purchased included 9000 gallons of port, 9000 gallons of Muscat, 6000 gallons of Sherry and 6000 gallons of Angelica.

After unsuccessfully attempting to sell the wine in California to said clergy, Marion hired an agent “who said he knew rabbis in Chicago” but alas, those rabbis had their own sacramental supply of wine. It is pure conjecture on my part, but could it be that the agent was one Ethelbert Favary?

Giannini contended that “Mrs. Brashears was aware of the situation when she signed the contract” and maintained that if their deal was in violation of the Prohibition laws, the court was not in a position to give relief to either side.

Judge J. A. Allen awarded “Mrs. M. W. Brashears” $5,600 with interest dating back to December of 1929. Giannini appealed all the way to the United States Supreme Court who refused to hear the case. The story is just another interesting chapter in Marion’s already interesting life.

In January of 1935 it was announced that Marion had sold her Palos Verdes home to Mr. and Mrs. James P. McDonnell. However, a 1936 directory lists Marion still living there with guests or boarders, Adolfo and Clara Di Segui, while her husband remained in Carlsbad. Perhaps the sale of the home fell threw or Marion demurred.

Death of Irving J. Gill

It has been assumed by some that Marion and Irving divorced, but no such action could be found in San Diego County Superior Court records, or in Los Angeles. (Reno, Nevada, “the divorce capital of the world” was also checked for divorce records and none were found.) It could be that the two remained friends, or were amicable with their separate living arrangements or that there was some estrangement. It is often noted, however, that Gill wrote loving letters to Marion while they were apart.

On October 7, 1936 Irving J. Gill died in a San Diego hospital after a long illness. It was reported that his wife Marion and a nephew, Louis J. Gill were at his bedside.

Irving was cremated but no one knew what became of his ashes. There has been speculation that Marion received and then scattered them. But Marion never took possession of her husband’s cremains. In 2023 the Irving J. Gill Foundation reported “Gill’s ashes have been sitting in a tin box, on a shelf, in a closet at the Cypress View mortuary in San Diego. The mortuary paperwork states that they are to be held until ‘family comes to pick them up.'” The IJG Foundation plans to provide Gill a proper burial and resting place in October 2024.

Marion remained in her Palos Verdes home as late as 1938, sharing or renting rooms to Jenny Mills, James and Frances McDonald, and Virginia Randall. (She was not found in the 1940 census, but in 1943 she sold the lots in Carlsbad’s Optimo Tract and was listed as living in Laguna Beach.)

Death of Marion and Fight for Her Estate

Marion’s first husband, James Bradley Brashears died in Indiana on January 30, 1944. He had moved from Chicago to Indianapolis in about 1935.

By 1946 Marion had moved to a home at 223 Avenue F in Redondo Beach. In the 1950 census she was living alone and her occupation was given as interior decorator.

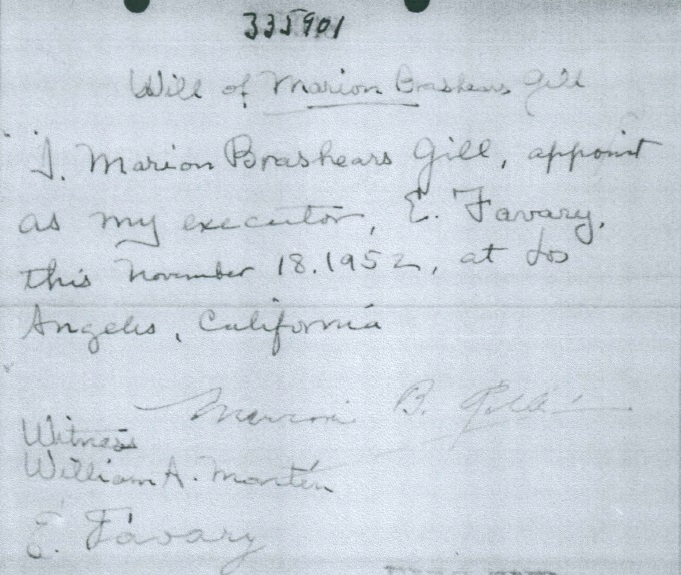

On December 1, 1952, at the age of 82, Marion died; just weeks earlier she had been declared mentally incompetent due to senility. Thus began a fight for her estate, valued at $25,000 that would be drawn out for years. Those who claimed a part of her estate included none other than Ethelbert Favary, who claimed to be Marion’s legal guardian.

Ethelbert had hand written a statement entitled “Will of Marion Brashears Gill” in which stated: “I, Marion Brashears Gill, appoint as my executor, E. Favary, this November 18, 1952, at Los Angeles, California.” The statement was purportedly signed by Marion and the witnesses were William A. Monten and E. Favary himself.”

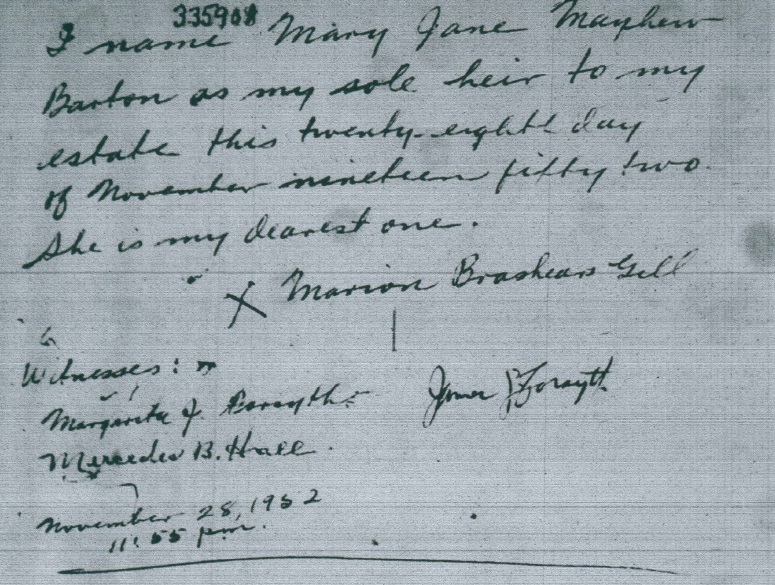

Ten days later, however, and three days before her death, Mary Jane Mayhew Barton drew up her own handwritten statement which read: “I name Mary Jane Mayhew Barton as my sole heir to my estate this twenty-eighth day of November nineteen fifty-two. She is my dearest one.”

Next to Marion’s name was an “X” as Marion was too physically frail (and likely incapacitated) to write at all. This statement was witnessed by Margaret and James Forsyth and Mercedes B. Hall. The Forsyths ran a nursing or convalescent home where Marion spent her last days.

It is inconceivable that neither party were thrown of court entirely for elder abuse for undue influence.

Mary Jane Mayhew Barton was a renowned harpist once under contract with Universal Studios and a member of the 20th Century Fox Orchestra, who played in several movie scores. Her relationship with or how she met Marion is unknown.

Barton claimed that Ethelbert and his wife Sadie had already gone through Marion’s house and taken away items in bags. Mary Jane claimed that she had her own money and income, insinuating that she did not need to go after Marion’s estate, but that it was rightfully hers because Marion had willed it to her.

A long-lost cousin from Canada was found by attorneys who claimed she was Marion’s closest living relative and therefore should be the rightful heir.

Marion’s probate case was discharged on January 27, 1959. The file contained over 400 pages. In the end, after the State of California, creditors and various attorneys got their share, Mary Jane Barton received what was left, but perhaps the most valuable, four lots in Palos Verdes Estates.

Marion was buried in Pacific Crest Cemetery in Redondo Beach. Her gravesite is unmarked. She was placed in a section designated for “unclaimed” or “unpaid” for people.

It seems Ethelbert Favary, whom she knew for over four decades, her supposed “legal guardian” and claimant to her estate, did not care to make sure Marion had a proper burial or marker. Certainly, Mary Jane Barton, who was the recipient of what was left of Marion’s estate and named herself to be Marion’s “dearest one,” could have seen to her burial.

No, Marion was forgotten, ironically like she “forgot” her husband Irving Gill; his ashes never claimed by Marion, sitting in a box for nearly 90 years.

The story of Marion has nearly been forgotten as well…but she was there waiting to be discovered. Scattered pieces of her life in newspapers, directories, lawsuits and other documents, all waiting to be gathered and assembled to tell her story.

While her marriage to Irving J. Gill made her notable, Marion Waugh Brashears Gill made her own headlines. She lived a fascinating, unconventional life on her own terms.

I want to thank Robin Kaspar for providing photos and information, along with the Oregon Historical Society, Julius J. Machnikowski, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County, the Peabody Township Library in Peabody Kansas, the National Archives and Records Administration, Los Angeles County Superior Court Archives, John Sheehan, FAIA Principal, Irving J. Gill Foundation. Research included documents obtained from the NARA, San Diego County Recorder’s Office, Los Angeles County Recorder’s Office, Circuit Court of Cook County, Los Angeles County Superior Court Archives, and more.