Have you ever wondered why a street you travel or live on has a certain name? Developers typically get to name the streets in their subdivisions and years ago streets were named after early landowners and pioneers.

Since several Oceanside street names were changed in 1996, it has been difficult for longtime residents to call Hill Street anything but Hill Street. Along with the name change of our beloved “main street” came new names to remember: Seagaze, Sportfisher, Neptune, etc. when First Street through Eighth Streets became a thing of the past. However, Second Street had been conspicuously missing for decades when it was changed to Mission Avenue back in the 1950s, and no one seemed to question why.

Although residents may still lament the loss of their beloved Hill Street since it was changed to Coast Highway, several street names have been changed over the years including Short Street to Oceanside Boulevard; Couts Street to Wisconsin Avenue and the Paseo Del Mar to The Strand, just to name a few. Pacific Street north of Fifth Street (Sportfisher now) was called Washington Street! Temple Street south of West Street is now South Nevada and Boone Street south of West Street was renamed South Clementine.

However, we can still celebrate the many street names that have been with us from the 1880s when Oceanside was being laid out and developed.

Cassidy Street in South Oceanside was named after Andrew Cassidy, an early San Diego County resident. According to a biography written by William E. Smythe in 1908, Cassidy “came to America when 17 and was employed three years at West Point, in the Engineering Corps.” He was stationed in San Diego in 1853 and was acquainted with Col. Cave J. Couts of Rancho Guajome, who also attended West Point. Cassidy served as a pallbearer at the funeral of Col. Cout’s widow, Ysidora Bandini Couts who died in 1897.

Cottingham Street is named after Louis Cottingham, a former city attorney and longtime Oceanside resident.

Couts Street west of the railroad was named after Cave Couts, Jr., who surveyed the new Oceanside townsite in 1883. Couts Street was changed to Wisconsin Avenue in 1927 as a continuation of that street.

Crouch Street was named after Herbert Crouch, a sheep rancher from Australia. Mr. Crouch settled in the San Luis Rey Valley in 1869. When Mr. Crouch came to San Luis Rey he engaged in the sheep business and “the present site of Oceanside at that time was used as a part of his grazing range.” Herbert Crouch was an historian in his own right and contributed many articles to the local newspapers. He also kept records of weather conditions and rainfall which were studied by the county weather bureau.

Downs Street was named after Ralph Downs who owned 26 acres in the Fire Mountain neighborhood. His son, Jim Downs remembered that City Engineer Alton L. Ruden, who was a friend of his father, surprised their family by naming the road “Downs Street” in the mid-1950s. In the 1960s the developer of a new subdivision submitted “Ups” Circle to the city planners as a joke. The street name was accepted which led to the amusing intersection of Ups and Downs.

Ellery Street is named after Henry Ellery who subdivided the tract which includes the Loma Alta neighborhood. In addition to being a real estate developer, Ellery owned a grocery store and operated a large bean warehouse here for many years. It is believed that the small street of Rose Place was named after the mother of Ellery’s wife, Ada.

Foussat Street was named after the Foussat family, particularly Hubert Foussat who came from France to San Diego County in 1871. His son Ramon lived near the area of the present day Foussat Street and Oceanside Boulevard. Ramon’s stepdaughter, Louise Munoa Foussat, was a Luiseno Indian who lived to be 97 years old. Louise Foussat now has an elementary school named after her.

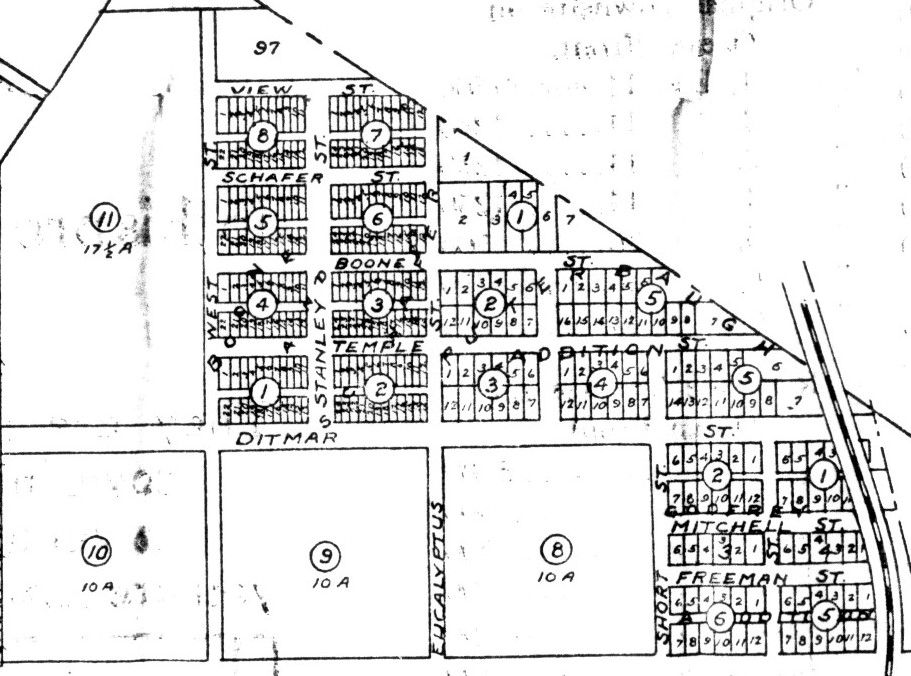

Freeman Street named after the Freeman family, were early pioneers of the San Luis Rey Valley who came from Texas in the late 1860s. Many members of this family are buried in the Pioneer Cemetery in San Luis Rey. Archie Freeman, son of Alfred A. and Permelia Freeman was a deputy constable and one of the first blacksmiths in Oceanside.

Hayes Street was named after John Chauncey Hayes, an early San Luis Rey Valley resident. Hayes was an attorney, justice of the peace, newspaper editor of the South Oceanside Diamond and real estate agent in Oceanside for several decades. His place in Oceanside history is disproportionate to the tiny little street that bears his name.

Hicks Street was named after James Van Renslear Hicks who came to California and settled in San Diego County in 1874. He served as Oceanside’s deputy sheriff and city trustee, as well as justice of the peace. In 1886, he joined John Chauncey Hayes and went into the real estate business.

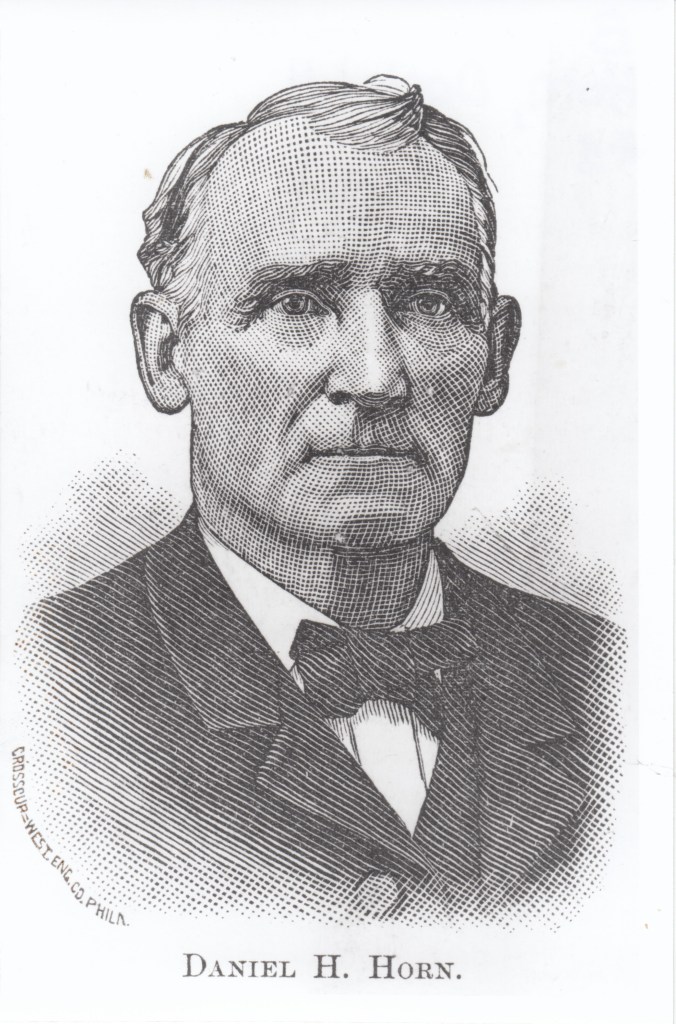

Horne Street was named after Col. Daniel H. Horne who came to Oceanside from Kansas around 1886. Col. Horne’s large home and property was located where the Mission Square Shopping Center is now, at Horne and Mission (then Second Street). He was Oceanside’s first mayor, or president of the City Trustees in 1888. Horne helped to found the state capital city of Topeka, Kansas, which is how Topeka Street got its name.

Hunsaker Street was named after Attorney William J. Hunsaker. Hunsaker was a partner in the law firm Hunsaker, Britt & Lamme. He represented John Chauncey Hayes in a suit against the City of Oceanside and also defended John W. Murray, who shot and killed Oceanside’s Marshal Charles Wilson in 1889.

Kurtz Street was named after Daniel B. Kurtz who came to San Diego County in 1850 and elected Mayor of Old Town San Diego in 1851. He settled in San Luis Rey in 1866 and served as Judge.

Lucky Street was named by and after Elgin “Lucky” Lackey. Lucky owned a café, then later Pacific Holidayland and developed small subdivision off of California Street in the late 1950s.

Machado Street was named for an early Spanish family. Mac and Juan Machado were in business with Louis Wolf in the early 1880’s.

Maxson Street was named after Charles W. Maxson who arrived in San Diego on March 24, 1886. Shortly afterward he came to Oceanside and joined with C. F. Francisco to open a general merchandise store. He later entered the real estate and insurance business with Ben F. Griffin. Maxson was also one of Oceanside’s first city trustees.

Mitchell Street was named after John Mitchell who came to Oceanside in 1887. He had previously lived in Fallbrook and planted extensive orchards there. He purchased property in Oceanside and owned a home on Pacific Street.

Myers Street was named after Oceanside’s founder, Andrew Jackson Myers. He first settled in the San Luis Rey Valley and in 1883 received a land grant of 160 acres. A. J. Myers hired Cave Couts, Jr. to lay out the townsite and together with John Chauncey Hayes developed the town of Oceanside and began the naming of our city streets.

Nevada Street was said to “bear the name of the daughter of one of the first settlers, a young lady who was the belle of the village in the late 80’s.” Nevada McCullough was the daughter of John and Mary McCullough. The McCulloughs moved to Oceanside in its earliest days and were said to be some of the first residents here.

Reese Street, is believed to be originally Reece Street, and was named after Oscar M. Reece who came to Oceanside in February of 1885 when Oceanside was said to have had only three houses. He began a general merchandise business with his brother and was later elected Justice of the Peace. He also engaged in the sale of real estate and was a notary public.

Short Street, named after an early attorney, Montgomery Short who arrived in Oceanside in 1886, extended eastward from the railroad tracks and ended at about Nevada Street. West of the railroad tracks the street was then labeled as McCoy Street after another early pioneer. In the mid-1960s Short and McCoy Streets were changed to Oceanside Boulevard.

Tait Street, which runs parallel to Pacific Street just south of Wisconsin Street, was named after Magnus Tait, an early pioneer and manager of the Oceanside Water Works in 1888. His home is still standing at 511 North Tremont Street.

Tyson Street bears the name of Samuel Tyson, one of the earliest settlers in our city. Sam claimed to have built just the second house in Oceanside, just after the city founder’s A. J. Myers.

Weitzel Street was named after Martin S. Weitzel, a pharmacist who brought his family to Oceanside in 1885.

Whaley Street was named after Francis Hinton Whaley, an early pioneer resident of San Luis Rey Township. He was born in Old Town, San Diego and is said to have been the first white child born there. Whaley was the Editor of the San Luis Rey Star newspaper in the San Luis Rey Township in early 1880’s. This newspaper was later moved to Oceanside and became the Oceanside Star, which then became the Oceanside Blade. The Whaley House in Old Town San Diego is one of the most haunted places in America.

Wilcox Street is named after Ray Wilcox, who was a manager of Oceanside’s early Safeway store in the 1920’s. He later opened a real estate office, Wilcox Investment Company, and went on to become Oceanside’s mayor in 1946.

So what is the origination of our beloved Hill Street? There’s no clear answer but it is probable that plagiarism was involved. Hill Street, Cleveland, Broadway, Tremont and Ditmar Streets are names found in the cities of San Diego and Los Angeles.

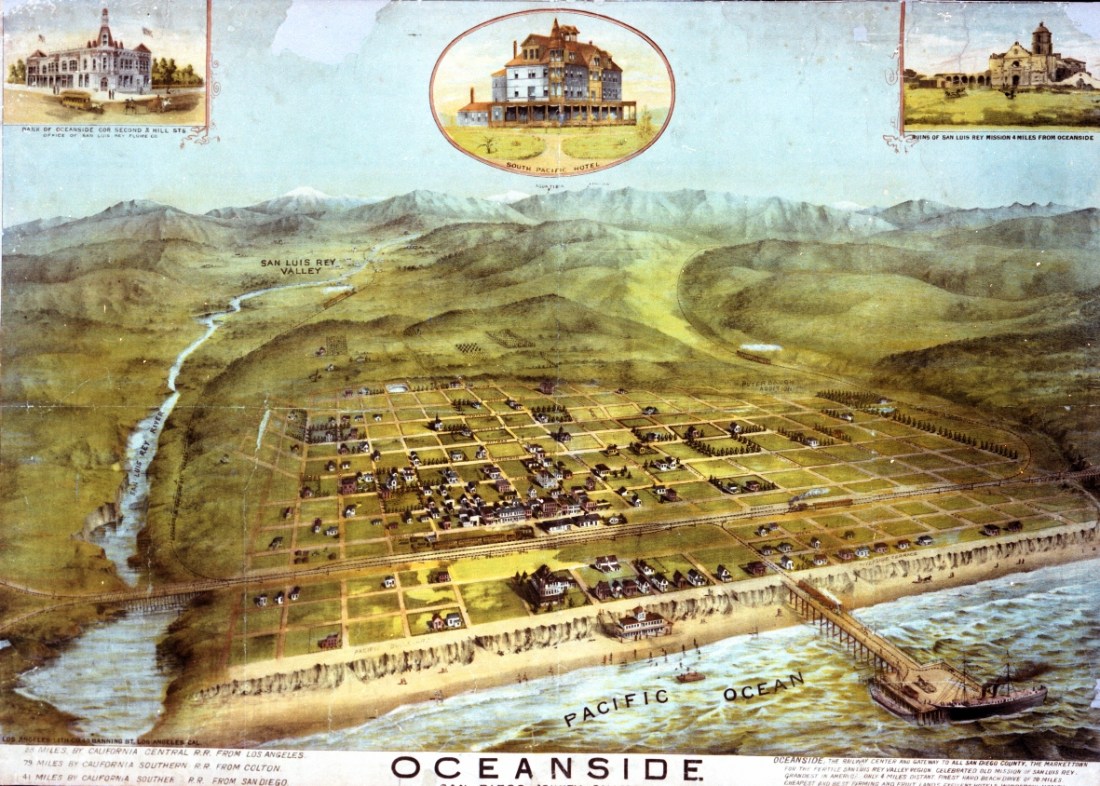

How did Oceanside get its name? In 1888 the South Oceanside Diamond newspaper reported that “whenever the families of the San Luis Rey Valley desired recreation and a picnic place” folks would simply suggest, “Let’s go to the ocean side.” In 1883 after a land grant was issued to founder Andrew Jackson Myers, he began to advertise his newly formed town of “Oceanside” as a seaside resort with miles of coastline.