Our City is made up of many different neighborhoods, often with their own unique characteristics, history and even architecture. As Oceanside’s population grew, its borders expanded with various subdivisions and new housing developments. From the exclusive enclave of St. Malo to Potter homes in South Oceanside and Francine Villa in North Oceanside, Oceanside neighborhoods are as diverse as the people who live here. Here are a few neighborhoods, some forgotten and others well remembered.

Guidottiville

Guidottiville was named by and after Amerigo Edwardo Guidotti. The area was near what is referred to as Lawrence Canyon just south of present Highway 76. Guidotti built his residence there along with several rentals and lived there for many years. The homes were removed by the 1980s to make way for the Highway construction.

Pine Heights

Pine Heights was a rather remote area of Oceanside, accessible only via Eighth Street, now called Neptune Way. Pine Heights provided expansive view of Oceanside and panoramic view of the Pacific Ocean. Niels Hansen, a local grocer, built a large Craftsman style home designed by noted architects the Quale Brothers in 1908. Also that year, Attorney John Johnston hired prominent Chicago and San Diego architect Henry Lord Gay, to design his $10,000 home in Pine Heights. The Hansen house was later moved to North Clementine Street but the Johnston home was demolished. Pine Heights is now the location of a 15-acre condo development by Evening Star Development.

North Oceanside Terrace

A new subdivision established in the late 1940s was situated along the northern most border of Oceanside along Camp Pendleton. North Oceanside Terrace includes Capistrano Drive, San Luis Rey Drive, Monterey and Sunset and other streets. Many of the homes built there were built in the early to mid 1950s and purchased by the military families that were stationed at Camp Pendleton. In 1953 the City approved Francine Villas to the east, adding over 300 homes. These homes were introduced as rentals to military and civilians with a two bedroom home renting for $72.75 and a three bedroom for $82.75. Because of the growing density and traffic, an additional entry into the neighborhood was provided, initially called “River Road”. Later Loretta Street from the Eastside neighborhood would be built across the San Luis Rey River to provide residents access. In 1955, construction of North Terrace Elementary School began, opening the following year. Today the area is more commonly referred to as Capistrano because of the area park.

South Oceanside

John Chauncey Hayes established South Oceanside, a small township just south of the City of Oceanside in the 1880s. In the earliest days it had its own bank, a school building, cemetery, several brick residences and a newspaper, the South Oceanside Diamond. This largely rural area included the Spaulding Dairy (established about 1913) and was home to acres of flower fields owned by the Frazee family and others. It turned residential when Walter H. Potter, “the man who built South Oceanside” began building dozens of small homes in 1947 that stretched from Morse Street to Vista Way.

Eastside

The Eastside neighborhood is just east of Interstate 5 and north of Mission Avenue, with entrance by Bush or San Diego Streets. The subdivisions of Mingus & Overman, Reece, Spencer, Higgins & Puls, which encompass the area, were mostly farmland when families from Mexico began settling there in the 1910s and 1920s. Most of the early residents were laborers who worked in the fields of the San Luis Rey Valley and the Rancho Santa Margarita (now Camp Pendleton). Many of the homes were built between 1920 and 1940 by the hardworking fathers and grandfathers of the families that still call Eastside their home. This neighborhood was referred to as “Mexican Village” by local officials but residents called it Posole. It was last neighborhood to have paved streets and a sewer system, which were not added until the late 1940s! Eastside was also the home of Oceanside’s first growing Black population in the 1940s and 1950s, along with Samoan and Filipino families.

Mesa Margarita

As Oceanside’s population grew at steady pace in the 1950s and 1960s, its borders continued to extend eastward. New housing was always in demand. Sproul Homes developed many new neighborhoods including Mesa Margarita, which is often referred as the “Back Gate” area because of its proximity to northeast entrance to Camp Pendleton. In 1965, 62 acres along North River Road were purchased by Fred C. Sproul Homes, Inc., a residential development firm, from Harold Stokes and Joe Higley. The Stokes and Higley families were long time dairy farmers in the San Luis Rey Valley. With the plan to build 275 new homes on the property it was one of several developments that changed the landscape of rural to suburban.

Oceana

One of the first adult only communities built in Southern California was that of Oceana. Situated east of El Camino Real and south of Mission Avenue, this planned community was built in 1964 at a cost of $25 million. It was touted as being “a city within a city” built on 180 acres with 1,500 lanai cottages and 300 apartments. At the time it was built it required that at least one adult be age 40 or over. A two bedroom, two bath model was listed at $16,995 and the community offered a variety of amenities which included a pool, golfing, library and restaurant.

Henie Hills

Henie Hills was owned by figure-skater Sonja Henie. Sonja and her brother Lief purchased 1,600 acres of ranch land in about 1941 which included the present day El Camino Country Club. In the early 1950’s the Henies began subdividing part of the land near El Camino Real at which time some of the first custom homes were built. A portion of this land was sold to Tri-City Hospital and eventually acquired by MiraCosta College. Miss Henie built a large house on Oceanview Drive, which she used during her visits here from her native Norway. She continued ownership of 350 acres until 1968. In the 1974 Henie Hills opened as one of the nation’s first planned residential estates community, offering homes on estate-size lots averaging one-half acre with views of the sea, mountains and golf fairways in the valley below. Home prices ranged from $54,000 to $81,000.

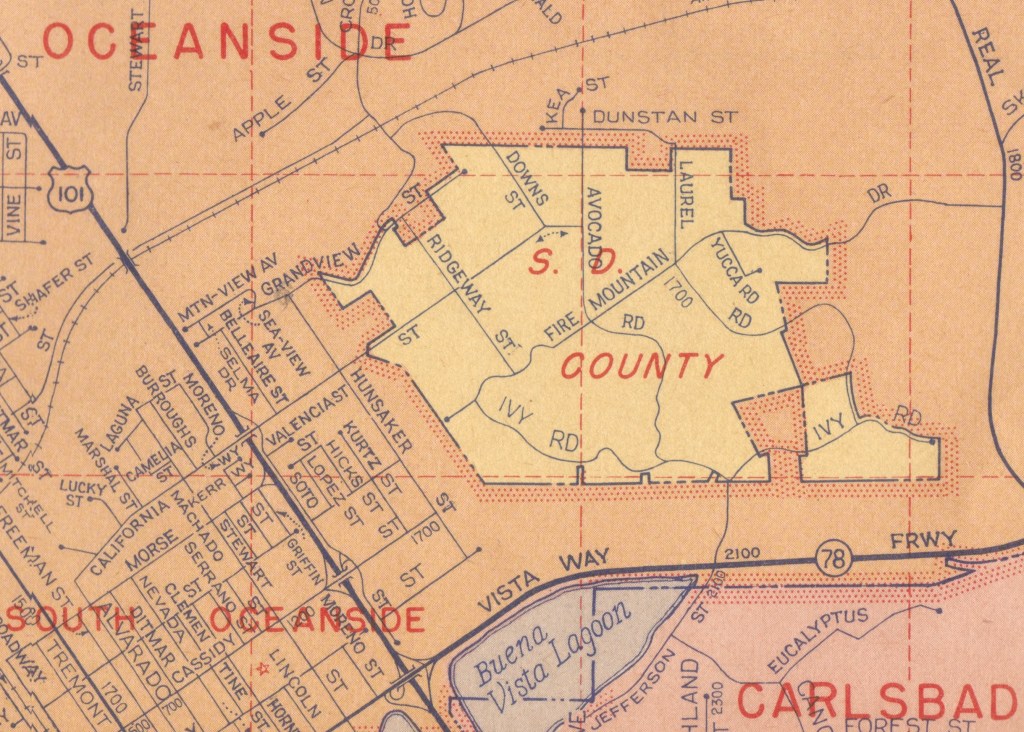

Fire Mountain

Fire Mountain was at one time called “North Carlsbad”. It was a largely rural area planted with avocado and citrus groves, consisting of approximately 338 acres. While the town of Carlsbad eventually grew and incorporated, North Carlsbad remained an unincorporated area of San Diego County, an island surrounded by the city limits of Oceanside. The City of Oceanside annexed the area in the 1960s. It has developed into a desirable neighborhood simply named after the road traveling through it, consisting of middle-class homes, tract and custom homes, many of which sit on large lots, some offering views of the Pacific Ocean.

St. Malo

A group of twelve homes was built by 1934 in an exclusive enclave in South Oceanside at the end of Pacific Street. Pasadena resident Kenyon A. Keith purchased 28 acres of oceanfront property and contained homes resembling a French fishing village that was known as St. Malo. Well-to-do property owners used St. Malo for vacation and summer homes. Early film director Jason S. Joy’s home was identified as “La Garde Joyeuse” and included an outdoor bowling alley and volley ball court. Author Ben Hecht was another resident, as well as Frank Butler, who co-wrote “Going My Way”. The beautiful community of St. Malo remains one of Oceanside’s best kept secret and continues to serve as summer homes and getaways for the rich and famous.

Plumosa Heights

Banker B.C. Beers established a new subdivision in the 1920s called Plumosa Heights, named for the plumosa palms lining the streets. This once exclusive neighborhood includes West and Shafer Streets, two of the street names are named for his children, Alberta and Leonard. The Plumosa Subdivision required at least a $4000 structure on the property to be set back at least twenty feet from the street. Plumosa Heights continues to be a desirable neighborhood with concrete streets and original cement light posts. Although it was the home of many affluent Oceanside residents, it was also inhabited by Oceanside’s middle class.