The pier fire on April 25, 2024 shocked residents of Oceanside, stunned to see clouds of black smoke covering the pier, and blanketing downtown. People lined Pacific Street, streaming live on social media as they watched the pier burn and firefighters battle the blaze. Scores of fire trucks, boats and air support were assembled as the black smoke billowed over downtown. As the fire raged on it seemed the pier would be lost. Smoke and flames continued through the night and daybreak. Emerging from the flames the Oceanside pier stands heavily damaged on the west end. But it still stands.

The Oceanside Pier has been built and rebuilt six times. It has become a part of our identity as a city. It is part of who we are and we feel emotionally connected to it.

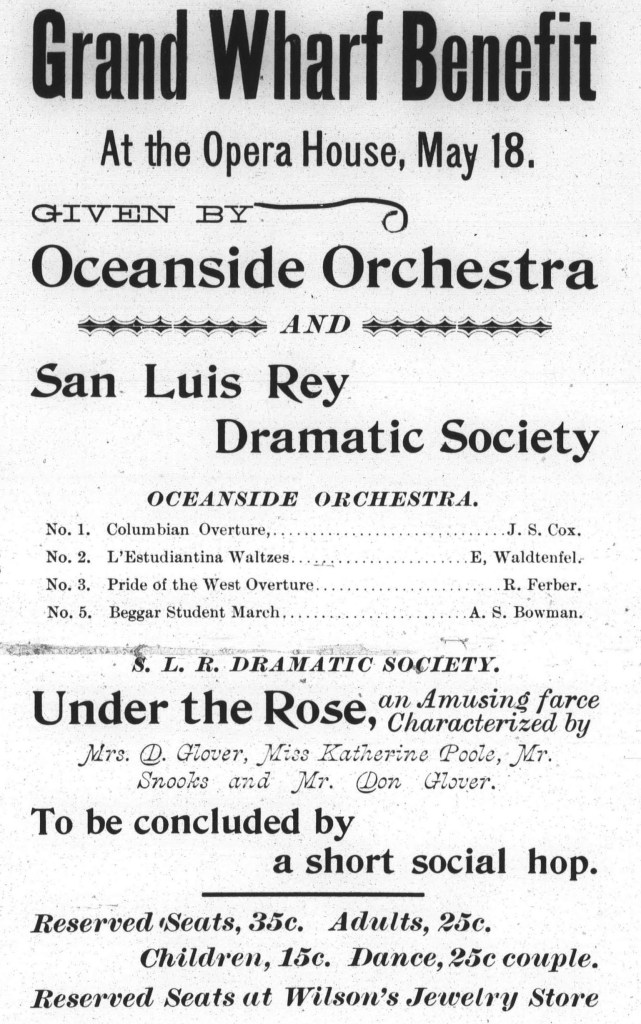

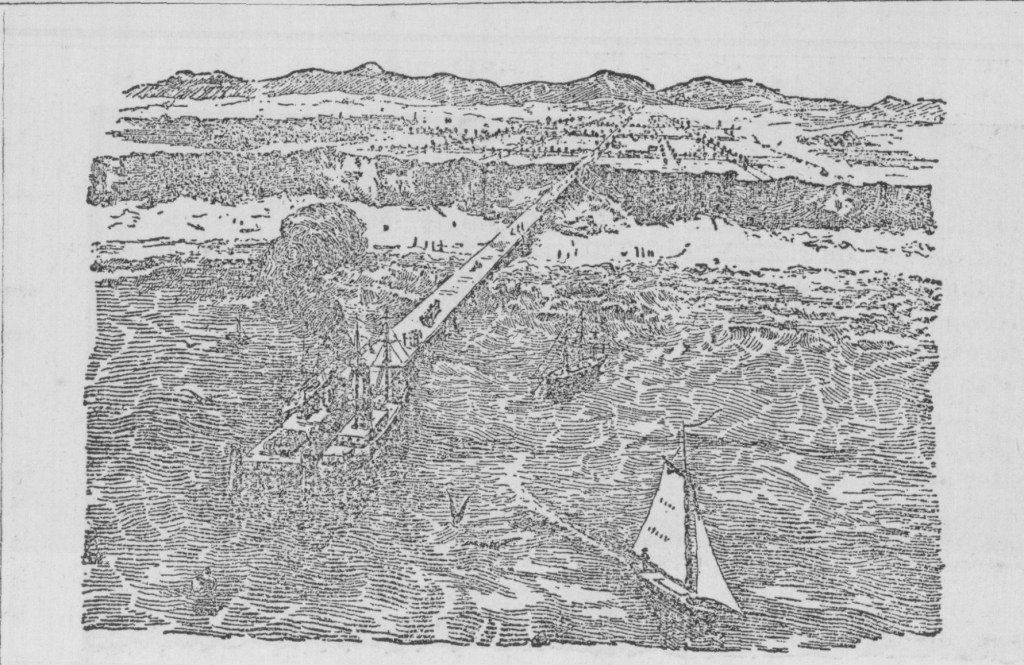

One hundred thirty-six years ago, our first pier was built in 1888 at the end of Wisconsin Street (formerly Couts Street). That same year Oceanside incorporated as a city. The first pier was called a wharf and it was hoped that Oceanside would become a shipping port. Built by the American Bridge Company of San Francisco, by August the wharf was built to an impressive length of 1200 feet. But the first pier was damaged by storms in December of 1890 and reduced to 940 feet. By January 1891 a larger stormed finished what was left and swept away all but 300 feet of Oceanside’s first pier and the beach was covered with its debris.

While short-lived, Oceanside was invested in having another wharf or pier. Melchior Pieper, manager of the South Pacific Hotel, initiated the idea of rebuilding as he gathered lumber from the first pier that had washed to shore and stored it behind his hotel on Pacific Street.

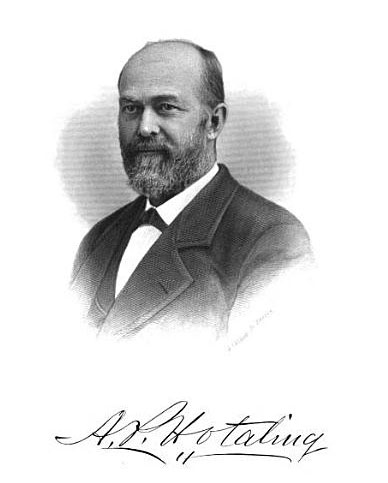

Pieper suggested that the pier be built at the foot of its present location, Third Street (now Pier View Way). There was some resistance against the Third Street location, a site between Second and Third was favored, but A. P. Hotaling, the hotel owner, agreed to donate $350 so city officials relented. Pieper donated an additional $100 and offered to house the workmen for free.

Oceanside’s second pier was completed in 1894. It was small, just initially 400 feet into the ocean, and braced with iron pilings, giving it the name of “the little iron wharf.” It was later extended a few hundred feet, but by 1902 it was damaged severely by heavy storms.

Residents were resolved to have a pier, however, and in 1903 Oceanside’s third pier was built. Supported by steel railway rails purchased from the Southern California Railway Co., it was nearly 1300 feet, later extended to 1400 feet. It was hailed as Oceanside’s “steel pier.”

Again, storms took a toll on our pier when in 1912 supports were swept away from the end of the structure, leaving the stumps of railway steel exposed. Since diving from the pier was allowed, this posed a danger. A warning sign was put in place to prevent divers from diving from the extreme end. By 1915 the steel pier which once seemed almost invincible, was down to a little more than 800 feet.

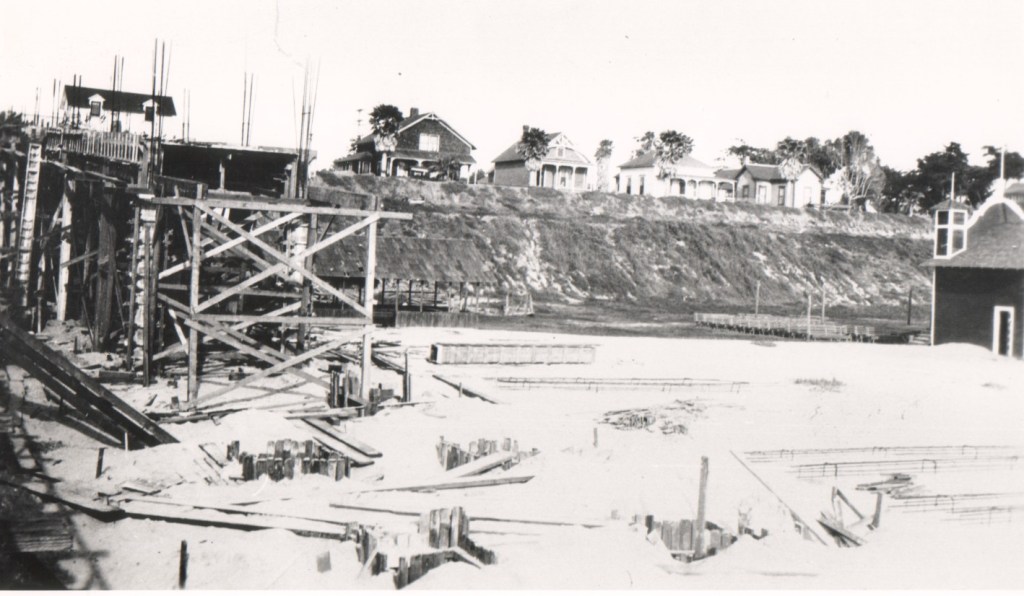

Voters approved a $100,000 bond issue in 1926 to build a fourth pier. In December of that year a single bid of $93,900 from Sidney Smith of Los Angeles was accepted and work began the same month. Compromises were made as to the construction of the pier as many had called for a concrete pier but the cost was prohibitive. Instead, a concrete approach was built, 300 feet long, with the remaining 1,300 feet built of wood. ( That same concrete portion is still used today, but it now needs to be rebuilt.)

When the 1600-foot pier was dedicated on July 4, 1927 Oceanside threw a three-day celebration that drew an estimated crowd of 15,000-20,000 to participate in the weekend of festivities.

By the 1940s it was evident that the fourth pier would have to be replaced. The pier that celebrated the roaring ’20s, and survived the Depression, had also aided in World War II. A lookout tower was erected on the end to aid in the search for enemy aircraft and submarines. The added weight of this tower left the pier weakened to a point where its safety was questioned.

Resident E.C. Wickerd, described as a “pier enthusiast”, circulated petitions in favor of saving the pier. He stated, “The pier has been one of Oceanside’s biggest advertising and tourist assets, and should be protected.” But with continuing heavy storms in 1945 and 1946, the pier was closed after being deemed unsafe by deep sea divers and engineers.

In late February 1946 the proposal was made for a bond election to reconstruct the Oceanside pier. Three hundred signatures were needed to get on the April 9th ballot. The needed signatures were collected and the bond election passed. The $200,000 bond would build Oceanside next pier in 1947 to a length of 1,900 feet –the longest on the West Coast.

The white-railed pier could take fisherman and pedestrians out farther than any of its predecessors. A 28-passenger tram operated by the city could take guests out to the end of the pier and have room enough to turn around. McCullah sportfishing took enthusiasts out to fishing barges anchored over the kelp beds a mile out. For years this pier stood longer than any other pier the city had built previous.

But piers do not last forever and after nearly 30 years, it was showing its age. In 1975 the pier was faced with closures after severe storm damage and in October, Public Works Director, Alton L. Ruden said that the “pier could collapse at any time, and it would cost more than $1.4 million to replace it. Some morning we’re going to wake up and there won’t be a pier. It can go in an hour. It’s like a string of dominoes. But it’s only during storms that it is dangerous and that’s why it’s closed, when necessary.”

After nearly 30 years, it fell victim to the relentless storms. It was damaged in 1976 by heavy surf and then a fire at the Pier Cafe caused further damage. The end of the pier was open, vulnerable, angled to the north and had to be amputated.

The pier was placed as “No. 1 priority in the redevelopment plans for downtown” but it would be over a decade before a sixth pier was built.

Funding of the pier came from the Wildlife Conservation Board, State Emergency Assistance, Community development, the State Coastal Conservancy and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The new pier proposed would be nearly 1,500 feet long and would include a restaurant, tackle shop, lifeguard tower and restrooms. The total cost, including the demolition of the 1947 pier, was then estimated at $3 million dollars.

In August of 1985 Good & Roberts, Inc. of Carlsbad was awarded the contract to restore the concrete portion from the 1927 pier. In early 1986 the construction contract was awarded to Crowely International of San Francisco, the same city that built our first wharf in 1888. The new pier was built 3 feet higher at the end than the previous piers. This was because the waves do their greatest damage there. By raising the end, the life of the pier could be extended.

Oceanside’s sixth and present pier was dedicated and formally opened September 29, 1987. At a cost of $5 million dollars the pier was 1942 feet long and deemed the longest wooden pier on the west coast. Engineers said it could last 50 years.

Our pier is a beloved landmark. A wooden promenade out to the ocean that hundreds walk every day, thousands each year. While there are other piers in a handful of coastal cities, our pier has been a testament to our resilience and determination.

The pier is synonymous with Oceanside. If history tells us anything, we can and will rebuild again. Will we see our seventh pier sooner than expected? If repairable, we will enjoy and appreciate this one for years to come. This isn’t the end, it’s only a new chapter in Oceanside Pier history.