I was recently asked about Ida Richardson of Rancho Guajome. Who was she? Who fathered her children? Where did she come from? These are some questions that have been asked for decades. Little to nothing could be found about her but after I found a few small clues, the hunt was on. What I discovered through vital records and recorded documents answers those questions and more.

Ida K. Richardson, who would inherit the Rancho Guajome in Vista, California, from Cave Couts Jr. after his death in 1943, was often referred to as his housekeeper or secretary. Others have suggested that she was his common law wife. Some historians believe that Couts fathered her two children, Belda and Earl. Because of this assumption, it is often cited that the historic Rancho was passed down to his “descendants.”

But were Belda and Earl really the offspring of Cave Couts, Jr., the “Last of the Dons”? What was the relationship between Ida and Cave? Who was the father of her children? Perhaps history will need to be rewritten as those questions now have answers.

Ida Kunzell Richardson was born June 3, 1898 in Ventura, California to William K. Richardson and Ida Kunzell Richardson. Her father was born in Leavenworth, Kansas and her mother in Germany. The couple were married October 14, 1897 and the Ventura Free Press published their marriage announcement under the headline “Married Before Breakfast.”

“Thursday morning, Reverend E. S. Chase, pastor of the Methodist Church was called upon to tie the nuptial knot making Mr. William K. Richardson of Randsburg, Kern County and Miss Ida Kunzell of this city, man and wife. The ceremony was performed before breakfast in order that Mr. and Mrs. Richardson might take the early train for their home at Randsburg.”

William King Richardson was 35 years old who worked as a miner. Ida was 25. (Their daughter Ida was born just 8 months later.)

While the newlyweds may have made their home in Randsburg, a mining town in Kern County, it appears they eventually returned to Ventura. Just 11 days after baby Ida Richardson was born there, her mother died, on June 14, 1898.

Little Ida went to live with her maternal aunt and uncle, Minnie and Smith Towne, while her father returned to Kansas. When he died in 1948 his obituary mentioned his only survivor was a daughter living in California. It is unknown if Ida ever saw her father again.

Ida was raised by her Aunt Minnie and her uncle Smith D. Towne, who was a blacksmith. In 1910, he and Minnie, along with their son Frank and niece Ida were living in Pasadena.

In early 1912 the Towne family, along with Ida, moved to Strathmore, Tulare County, California. Sadly, soon afterward, Ida’s aunt and surrogate mother, Minnie Kunzell Towne, died February 21, 1912. The Tulare Advance Register published her obituary:

“Mrs. Minnie Towne, wife of S. D. Towne, who resides 8 miles west of Tulare, passed from this life this morning at 2:30 and the funeral will take place tomorrow afternoon at 1:30 from the Goble undertaking parlors. The body will be shipped to Oakland for cremation. The deceased was 47 years, 11 months and six days of age and was born in Germany. Mr. Towne and his wife are newcomers to this section, having recently come from Los Angeles.”

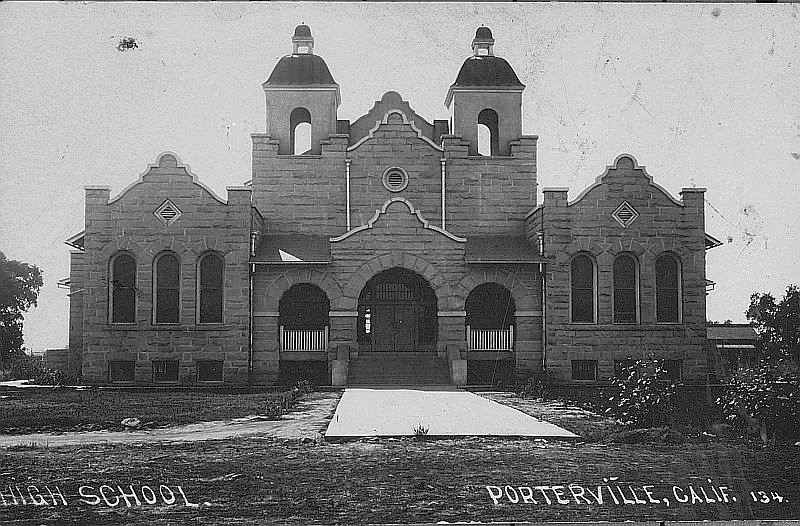

Ida Richardson was not yet 14 years old when her Aunt Minnie died. She continued to live with her Uncle Smith Towne and local newspapers referred to her as Ida “Towne.” She and her cousin Frank attended high school in nearby Porterville.

While in school Ida was noted for her writing skills. In 1916 she came in 2nd place for an essay entitled “Alcohol and Tobacco”, a piece on the dangers of such, for the Porterville Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The organization campaigned against alcohol, advocated for abstinence, and also supported women’s suffrage. Ida won $2 for her writings. Another essay she wrote that year, called “Peace and War” about the futility and despair of war, was published in the Porterville Recorder May 15, 1916. She graduated from high school in June of that year.

Ida was included in several of the personal notes and columns in the newspaper, which included her trips to the mountains or visiting friends.

On Monday, May 7, 1917 readers of the Porterville Recorder would read that a Fred C. Wehmeyer of Success (another small town in Tulare County) had left for Los Angeles to get married. It was reported that his bride was “a Strathmore woman.” Who was Wehmeyer’s bride?

The newspaper revealed two weeks later that “Mr. and Mrs. F. C. Wehmeyer of Success, who returned recently from a wedding trip to Southern California, were given a merry charivari by their friends a few nights ago. Mrs. Wehmeyer was Mrs. Miss Ida Towne of Strathmore.”

The following morning, a correction was published in the newspaper stating “It was Miss Ida Richardson of Strathmore, and not Miss Ida of Towne, who became the bride of F. C. Wehmeyer of Success recently.” Ida, who was raised with the Townes, did not mind to be included under the Towne family name for years, but her legal name of Richardson was used for her marriage and the clarification was made and noted.

The Los Angeles Times published a list of marriage licenses issued on May 7, 1917 which included Fred and Ida’s. Fred was listed as 44 years of age, while Ida’s age was 23. However, Ida was just a month shy of her 19th birthday and Fred was actually 56, near her father’s age.

The couple may have intentionally tried to disguise their age gap on the marriage application. Subsequent census records, however, were consistent with Fred’s birth year of 1861.

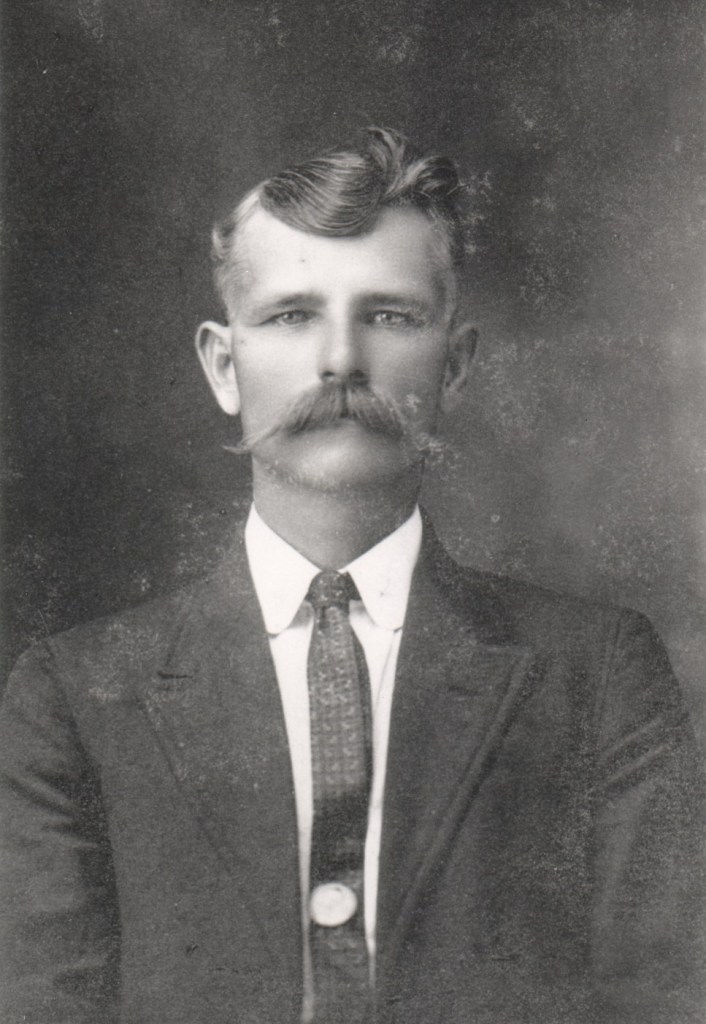

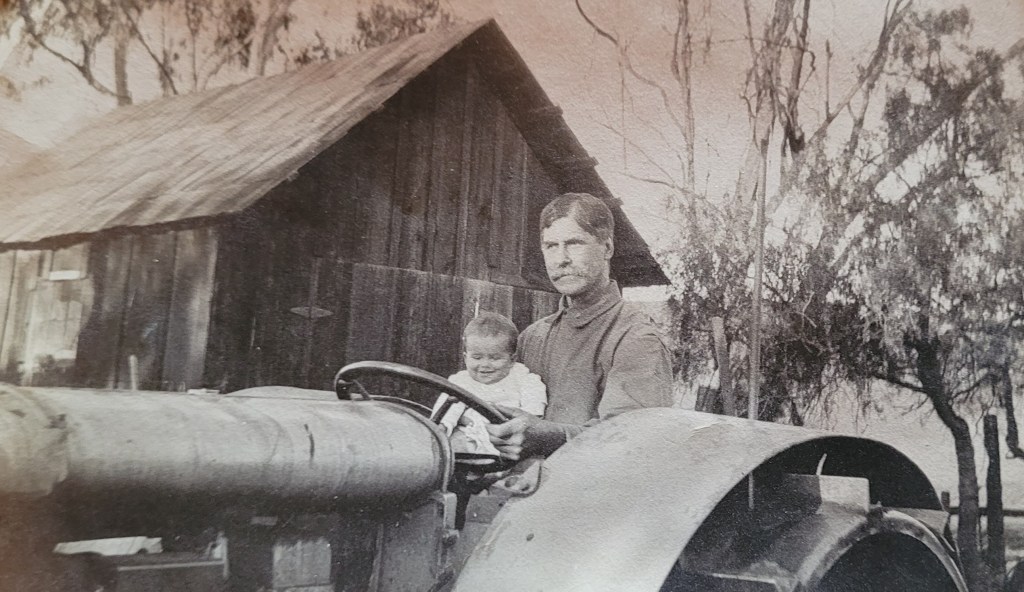

Frederick Christian Wehmeyer was born February 21, 1861 in Elkhart, Indiana. He first married Annie Bowlan in 1887 in Fresno, California. They had one son, Frederick Francis Wehmeyer, born in 1888. The two divorced and his son presumably stayed with his mother. (He was later living with an aunt in 1910.) Fred C. Wehmeyer remarried in 1896 to Lena Rogers, who died in May of 1916.

By the summer of 1919, Fred and Ida had moved to Vista, California and were living on or near the historic Rancho Guajome where Fred was working as a farmer.

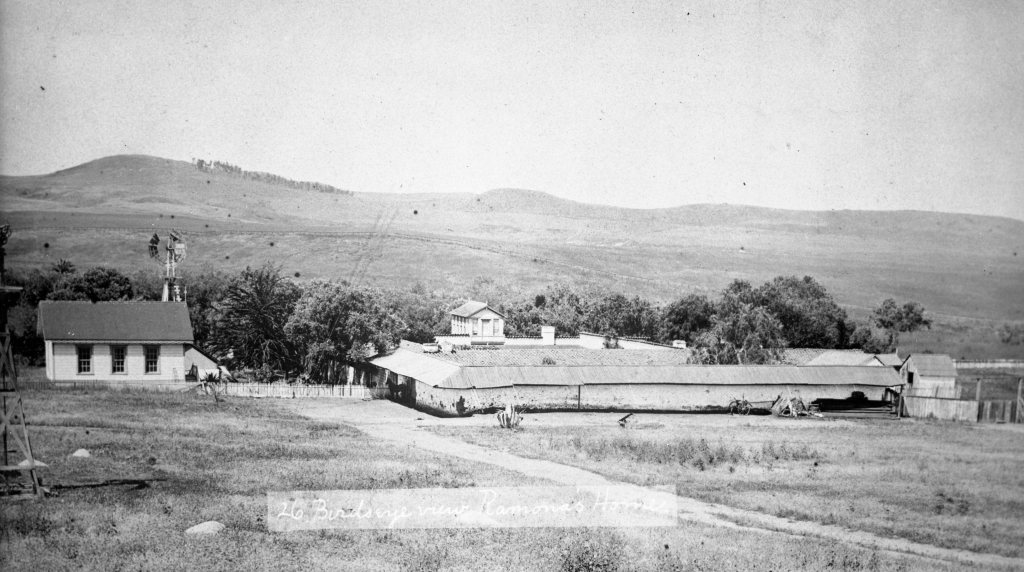

Rancho Guajome is an important historic landmark in San Diego County, once the home of Col. Cave Johnson Couts and his wife, Ysidora Bandini. The rancho was given to the couple as a wedding gift. Couts designed a large Spanish-style ranch house built by local Native Americans, made of thick adobe walls. The ranch house, with 7,680 square feet of living space and 20 rooms included a dining room, study, pantry, a kitchen, and eight bedrooms. Cave and Ysidora had ten children, eight who lived to adulthood, and were raised at Guajome.

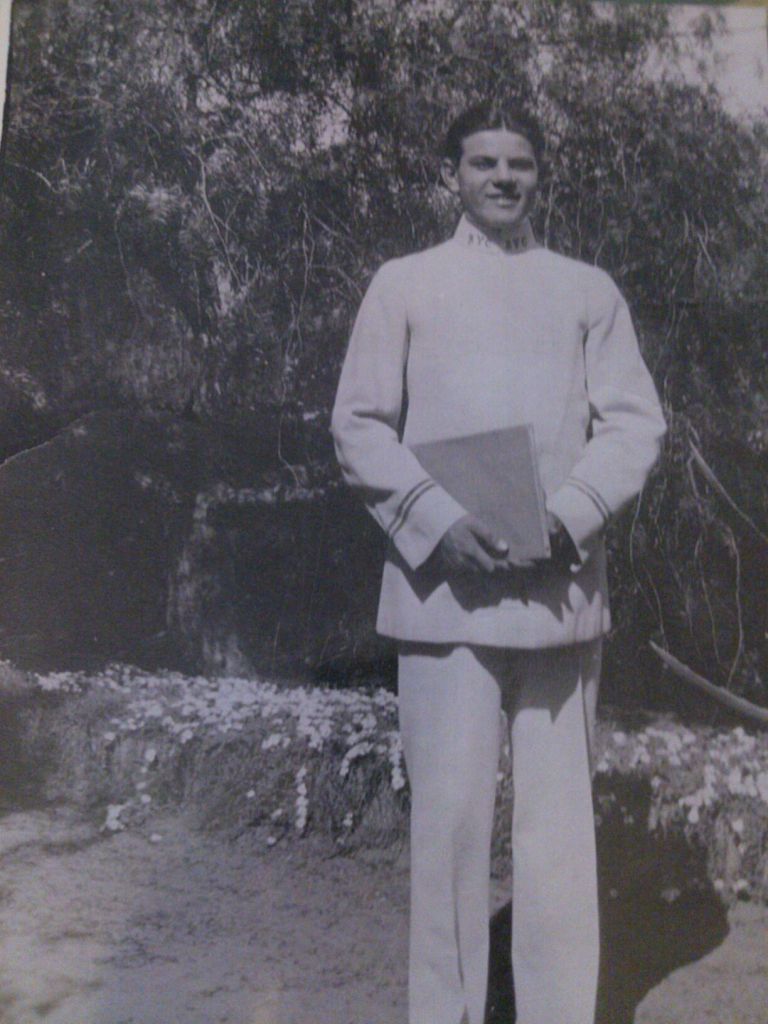

Col. Couts’ namesake, Cave J. Couts, Jr. was born 1856 and lived most of life on the Rancho. At the age of 20 he was deputy city engineer in Los Angeles, and was one of the first engineers of the California Southern Railway in San Diego. He went on surveying trips for the Southern Pacific Railroad and was one of the engineers that made the first surveys for the Panama and Nicaragua canals. Couts also surveyed the new town of Oceanside and laid out streets.

Cave Couts, Jr. hired Fred Wehmeyer to work on the Rancho, where he and Ida may have lived as well.

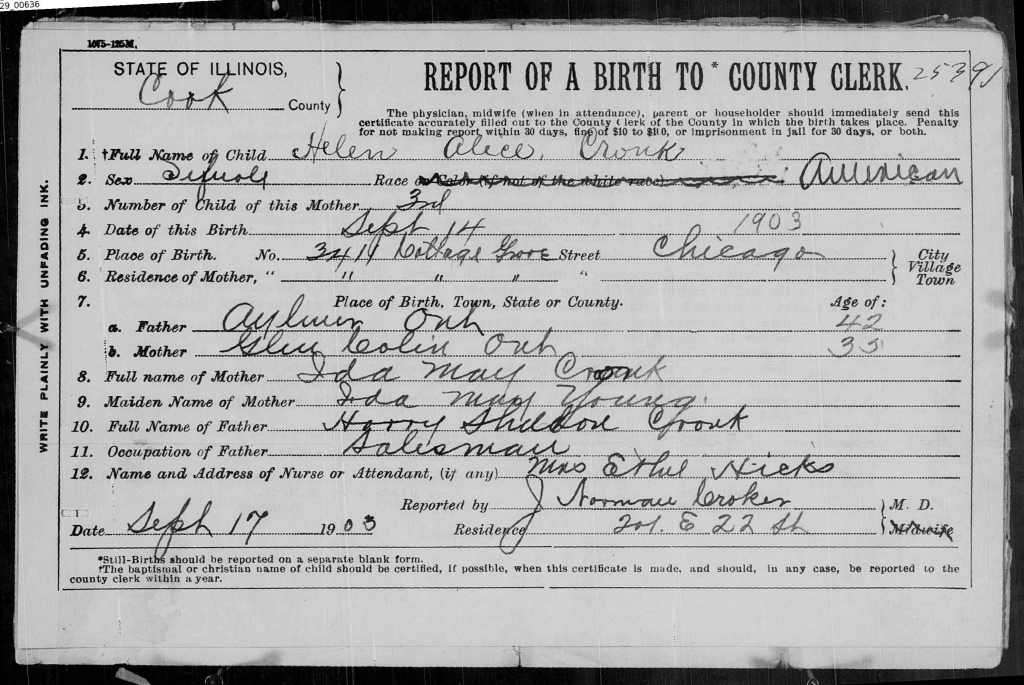

On August 8, 1919 Ida and Fred welcomed their first child together, whose name appears on the birth certificate as Elnor Kunzell Wehmeyer. (Fred’s age is off by 10 years but was likely provided to the recorder as such.) The baby was delivered by Dr. Robert S. Reid, a well-known and beloved Oceanside physician.

In the 1920 census Fred and Ida’s daughter has been renamed Belda.

The following year on October 13, 1920, Ida gave birth to a son whom she named Richardson Wehmeyer. Dr. Reid once again made the house call to deliver this baby.

On October 14, 1922 the Oceanside Blade noted that “Mr. and Mrs. Fred Wehmeyer of Guajome Ranch were in Oceanside Tuesday.” Fred was employed by Cave Couts as ranch foreman.

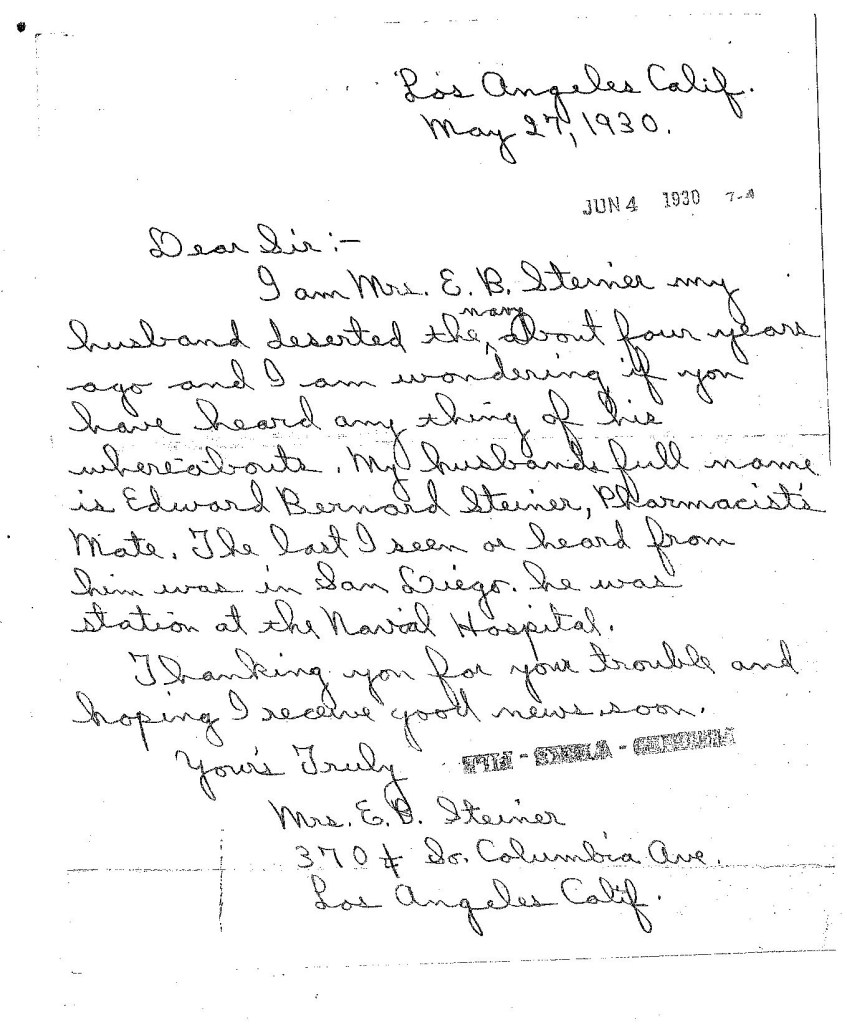

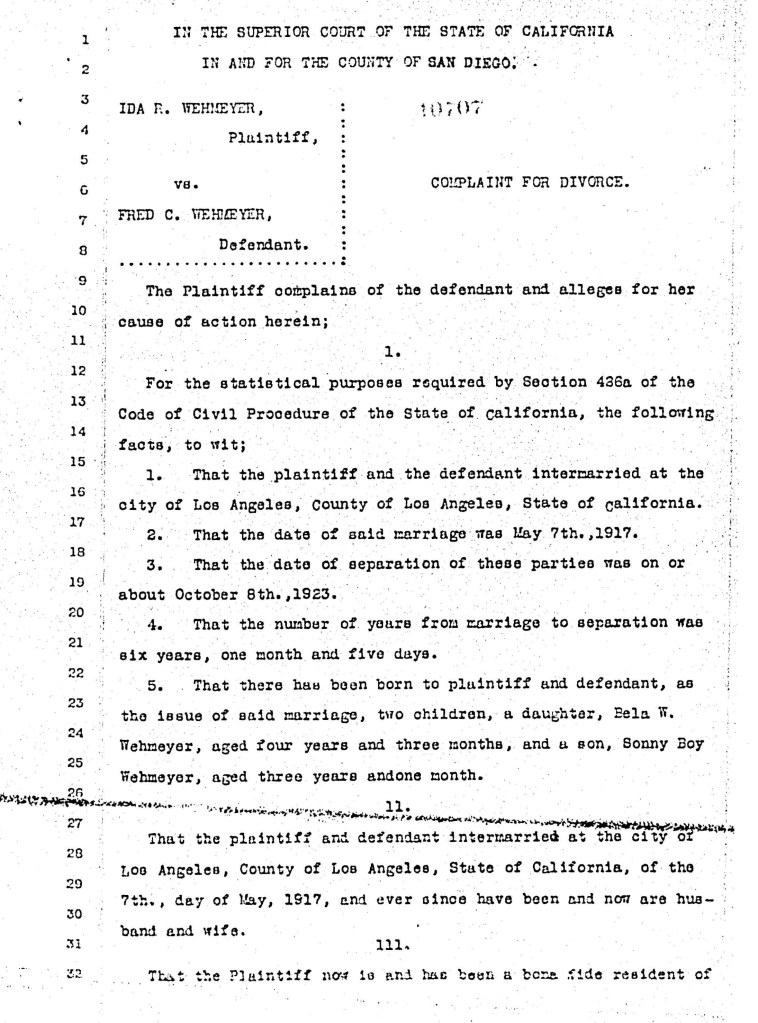

Ida filed for divorce on December 1, 1923 in the Superior Court in San Diego. In the complaint for divorce she stated that she and Fred were separated on about October 8, 1923. The number of years from marriage to separation was given as 6 years, 1 month and 5 days.

The divorce complaint also states that the marriage produced two children: a daughter, “Bela” Wehmeyer, aged 4 years and 3 months, and a son “Sonny Boy” Wehmeyer, age 3 years and 1 month.

Ida stated that Fred had “disregarded the solemnity of his marriage vows for more than one year” and had failed and neglected to “provide for the common necessaries of life.” She further stated she had to “live upon the charity of friends” although Fred was capable of making “not less than $100 per month” and more than able to support her.

Local rancher Sylvester Marron served the complaint upon Fred Wehmeyer on December 4, 1923. It appears that Fred did not respond to the complaint and a default was entered. Fred was ordered to pay child support of $20 per month and the children would remain with Ida. The final judgment of divorce was not entered until February 26, 1925.

Was this charity that Ida noted in her divorce papers coming from Cave Couts? It is likely. However, that did not mean Couts terminated his friendship or working relationship with Fred Wehmeyer as he continued to work at Guajome. Couts even sold Fred property in 1925.

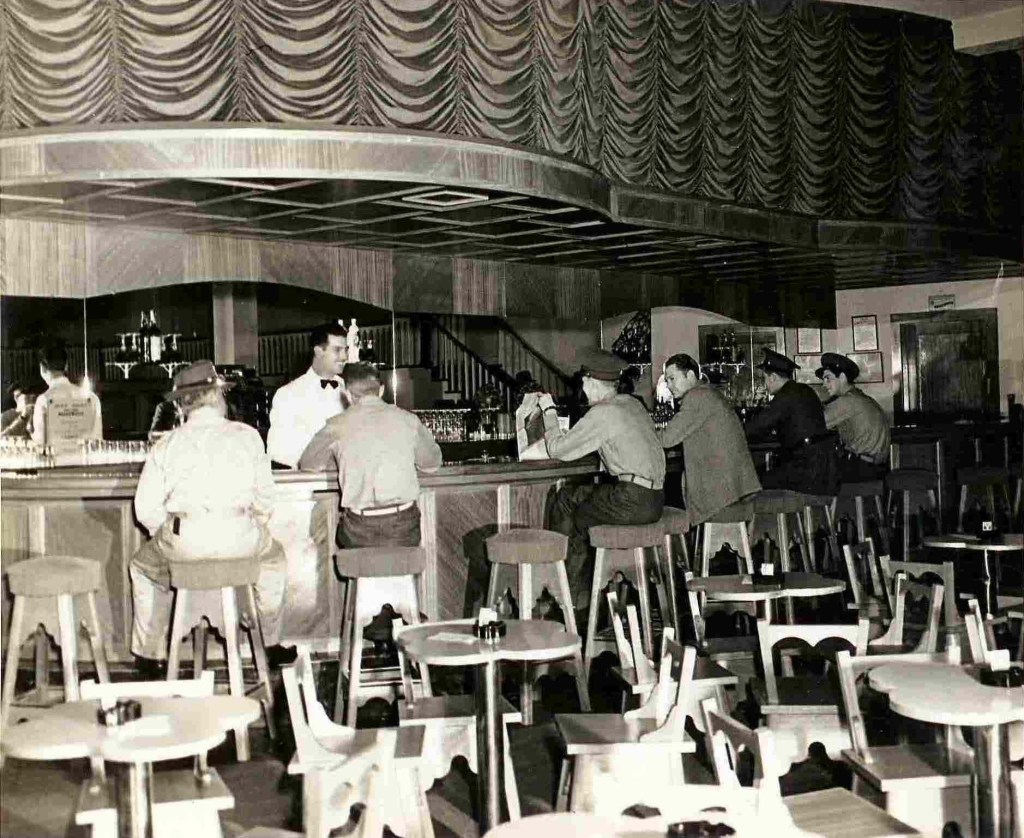

The North County Times reported on April 13, 1925 that an excursion of eight automobiles took a number of passengers to tour various parts of North San Diego County on Easter Sunday. They traveled to the San Luis Rey Mission, the Rosicrucian Fellowship and Rancho Guajome. J. B. Heath, author of the column, wrote that “At the Guajome ranch, buildings of which, covering two acres of ground, have just been restored at an expense of $20,000. The people were shown every attention by F. C. Wehmeyer foreman, in the absence of the owner.”

After the divorce it is likely that Ida returned her surname to her maiden name of Richardson. But she also changed the children’s names. Elnor was changed to Belda, and Richardson was changed to Earl. (To reiterate, the divorce record filed by Ida gave their names as Bela and Sonny Boy.)

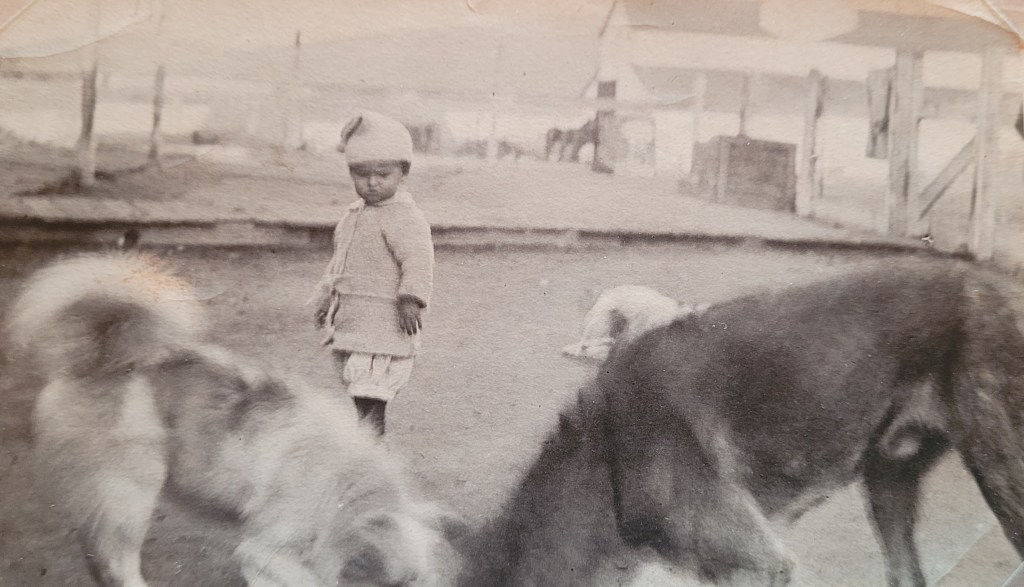

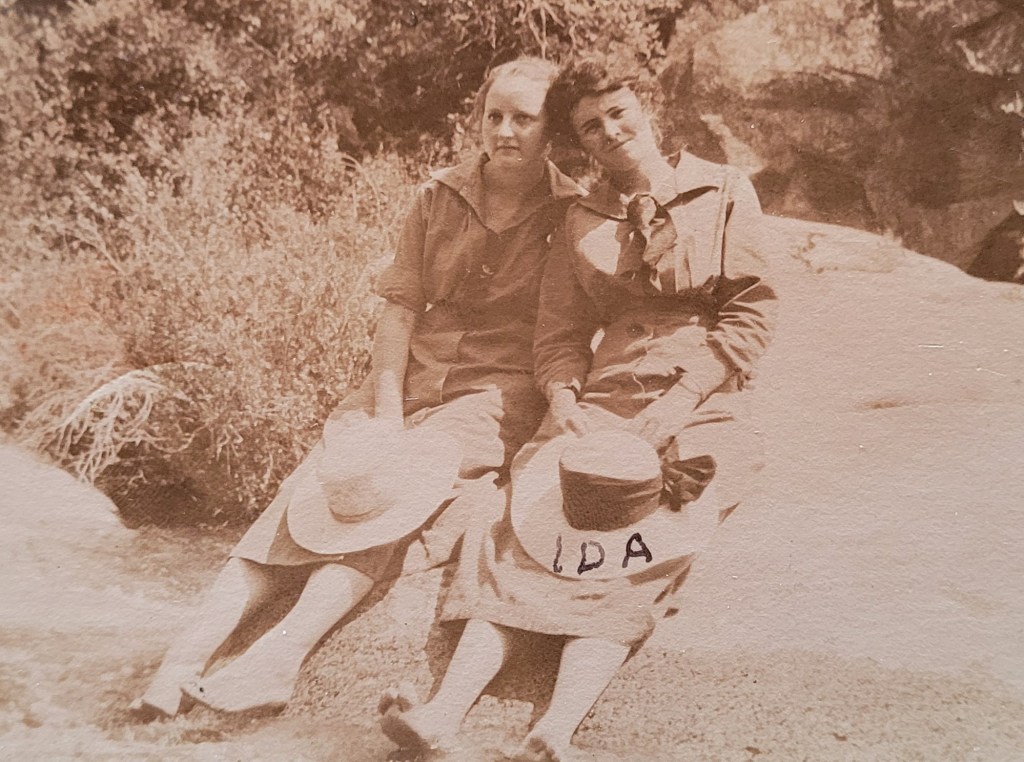

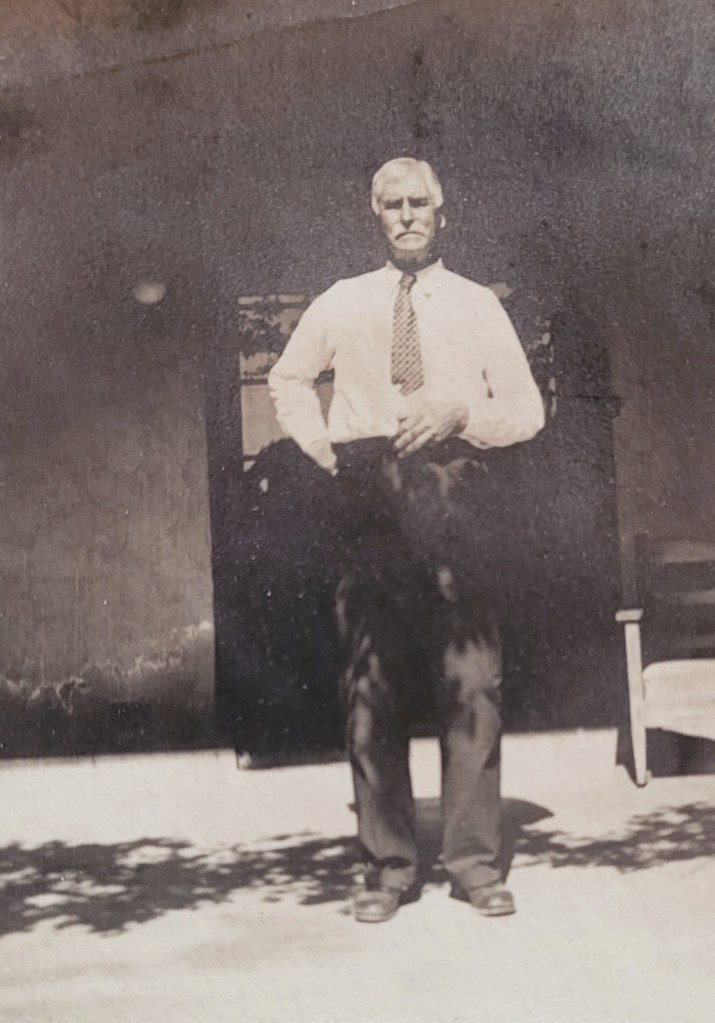

There are no public images of Ida but two photographs of Ida and her children were included in a 2008 book entitled “Ranchos of San Diego County” by Lynne Newell Christenson Ph.D. and Ellen L. Sweet. Ida is clearly a beautiful woman, and the images show the rancho in the background. The children appear to be 2 and 3 years old.

In the 1930 census, Ida and her children were living with Cave Couts at Rancho Guajome and listed as his adopted daughters and son. It is very doubtful that there was such an adoption, but that this relationship was listed as such for the census records or taker.

Fred Wehmeyer, listed in the same census district, was living on the property he purchased from Couts, just two miles south of Rancho Guajome, and operating a fruit farm. It is telling that Fred continued working for Cave Couts while Ida and her children lived on the rancho. Couts obviously maintained a relationship with both.

On September 22, 1930 the North County Times reported that Wehmeyer was working for Couts to restore the Bandini home in Old Town.

“Cave Couts, who owns the old Bandini home at Old Town San Diego, has been having it thoroughly repainted and renovated. It is one of the historical places in the bay section and Colonel Couts is making of it a lasting monument. Nearby and in the next block to the famous Ramona’s Marriage place, Colonel Couts has built a court of adobe enclosing an entire block. It has 40 double apartments surrounding a center court. The work has been in progress for several months. F. C. Wehmeyer of Vista has been employed on the big construction job.”

Belda Richardson attended local schools and graduated from San Diego State College in 1940. On August 30, 1941 she married Millard “James” Marsh in Yuma, Arizona. James Marsh was a native of Indiana, born in 1914 and was employed as a photographer. After three years in San Diego, the couple relocated to San Francisco, living at 1 Jordan Avenue in the downtown area.

Belda divorced James in 1946 and continued to reside in San Francisco. James Marsh moved to his parents’ home in Fallbrook and two years later took his own life.

Earl Richardson married Geraldine Morris, the daughter of local businessman Oliver Morris. The couple had three children.

Upon the death of Cave Couts in 1943, his obituary stated that “his secretary, Mrs. Ida Richardson, managed all his affairs, according to the son and only child, Cave J. Couts III, 4188 Arden Way.” (Couts only marriage was to Lilly Bell Clemens, niece of Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, and was a tumultuous one, ending in a bitter divorce and custody battle.)

In a variety of accounts Ida has been listed as a housekeeper, secretary and even common-law wife of Cave Couts. Respected historians have agreed with suggestions that Belda and Earl were fathered by Couts.

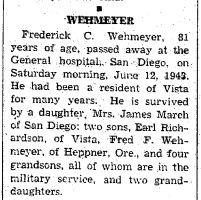

While Cave Couts died July 15, 1943, Fred C. Wehmeyer died one month earlier on June 12, 1943. His obituary, which ran in the Vista Press stated that he was 81 years old (he was 82) and had passed away at the general hospital in San Diego. It went on to state that:

“He had been a resident of Vista for many years. He is survived by a daughter, Mrs. James March (sic) of San Diego; two sons, Earl Richardson, of Vista, Fred F. Wehmeyer of Hepner, Oregon, and four grandsons, all of whom are in the military service, and two granddaughters.”

Belda and Earl had grown up on Rancho Guajome with their father living just two miles away. Surely, they saw him working as foreman on the very ranch on which they lived. Fred knew of his children, and the marriage of his daughter. They were included in his obituary. Did they remember and acknowledge him? Did they read this obituary?

It is apparent that Fred Wehmeyer was not lost altogether to history but somehow Ida had managed to erase him from her life and that of her children. Did Ida ever offer information as to how she came to Vista? How she ended up at the Rancho Guajome? Did she every mention Fred Wehmeyer to anyone in her many interviews? Did she clarify the rumors or innuendos that her children were fathered by Cave Couts?

In an article written by Iris Wilson Engstrand and Thomas L. Scharf for the San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 1974, Volume 20, Number 1, entitled “Rancho Guajome, a California Legacy Preserved” the historians write that: “The will of Cave Couts Jr. provided that Rancho Guajome would pass to Mrs. Ida Richardson as a life estate —because of her loyalty and faithful service. Mrs. Richardson, who moved to the rancho in the 1920s as a housekeeper, became the constant companion and helpmate of Couts. She was the mother of his two youngest children, Belda Richardson, who died in 1971, and Earl Richardson, final heir to Rancho Guajome, the place of his birth.”

County historian Mary Ward also believed the children were Couts’ and that “successive generations of Couts heirs resided in the ranch house until 1973.” It seems no one knew that Fred Wehmeyer existed and he may have never been mentioned again by Ida.

When Belda Richardson Marsh died May 16, 1970 in San Francisco, at the age of 50, it was her brother Earl who was the informant on her death certificate. On the certificate Earl does not provide the name of Belda’s father, instead he simply put “No Record.”

While Earl was just five years old when his parents’ divorce was final, did he not remember his father? Did he not see his father when he was working on Rancho Guajome for several years? Did Earl ever see or have his original birth certificate which clearly states his father as Fred Wehmeyer? Or did Ida hide this information from him? What is telling, is that he did not list Cave Couts, Jr. as her father. So Belda and Earl presumably did not know who their father was and did not believe him to be Couts.

Researchers and genealogists have not been able to obtain information on the children’s births for decades, and the identity of their father, because their last name was changed by Ida many years ago.

Ida and her two children died within four years of each other. Ida Kunzell Richardson died November 15, 1972. Her obituary states that she had lived in Vista for 74 years, but it was actually 55. Earl Richardson died December 4, 1974.

Interestingly, Fred C. Wehmeyer’s son, Fred F. Wehmeyer, eventually came to live in Vista and died there in 1973. After his father’s death in 1943, Fred Francis, apparently unable to remain silent about his father, who had been forgotten by his two younger children or their memories of him erased by their mother Ida, wrote a loving eulogy that was printed alongside his father’s obituary.

A Son’s Tribute to His Father

“Dad was a great man, that simple greatness that encompassed all the old-fashioned, homely virtues, now considered obsolete by so many. As James Whitcombe Riley once described a friend, “his heart was as big as all outdoors.”

Born on an Indiana farm of a father who had fled Europe to escape Prussian tyranny as far back as 1837 and to a mother of Pennsylvania Dutch origin, he became a true pioneer, for he marched in the Vanguard of civilization as it pushed its way westward through Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, California, and Washington.

In later life, he returned to California, which, in his mind at least had developed to become the greatest state in the union. He loved California, especially that part of San Diego County around Vista and never tired of extolling its virtues.

In wealth, his friends were legion, in poverty they were few but more sincere. He never whined about the fickleness of fate or harbored a grudge against the vicissitudes of life. He never used harsh words or even thoughts for those who had betrayed him or expressed more than mild rebuke about those who had openly robbed him.

As a youth, his strength and agility gave rise to many Paul Bunyanesque tales along the frontier borders. A mighty man, his true feats of strength became greater with the retelling by admirers. Personally, he was modest, and I never heard him brag of himself; he was a clean spoken man, never given to profane or obscene language.

He died in his 83rd year, facing death as fearlessly as he always faced life.

He has now stepped through those somber shadows that curtain the future of all life. I am very proud to be his son.”

Fred F. Wehmeyer

In spite of this loving tribute which defended his father’s integrity and his memory, Fred C. Wehmeyer was forgotten in the history of Vista and Rancho Guajome. His family name was removed from his children Belda and Earl, and nearly lost altogether. It is my privilege to tell his story, along with Ida’s, so that history can be amended and even restored.

Kristi Hawthorne, Oceanside Historical Society

Learn more about the history of Rancho Guajome and the Couts family: https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1974/january/guajome/